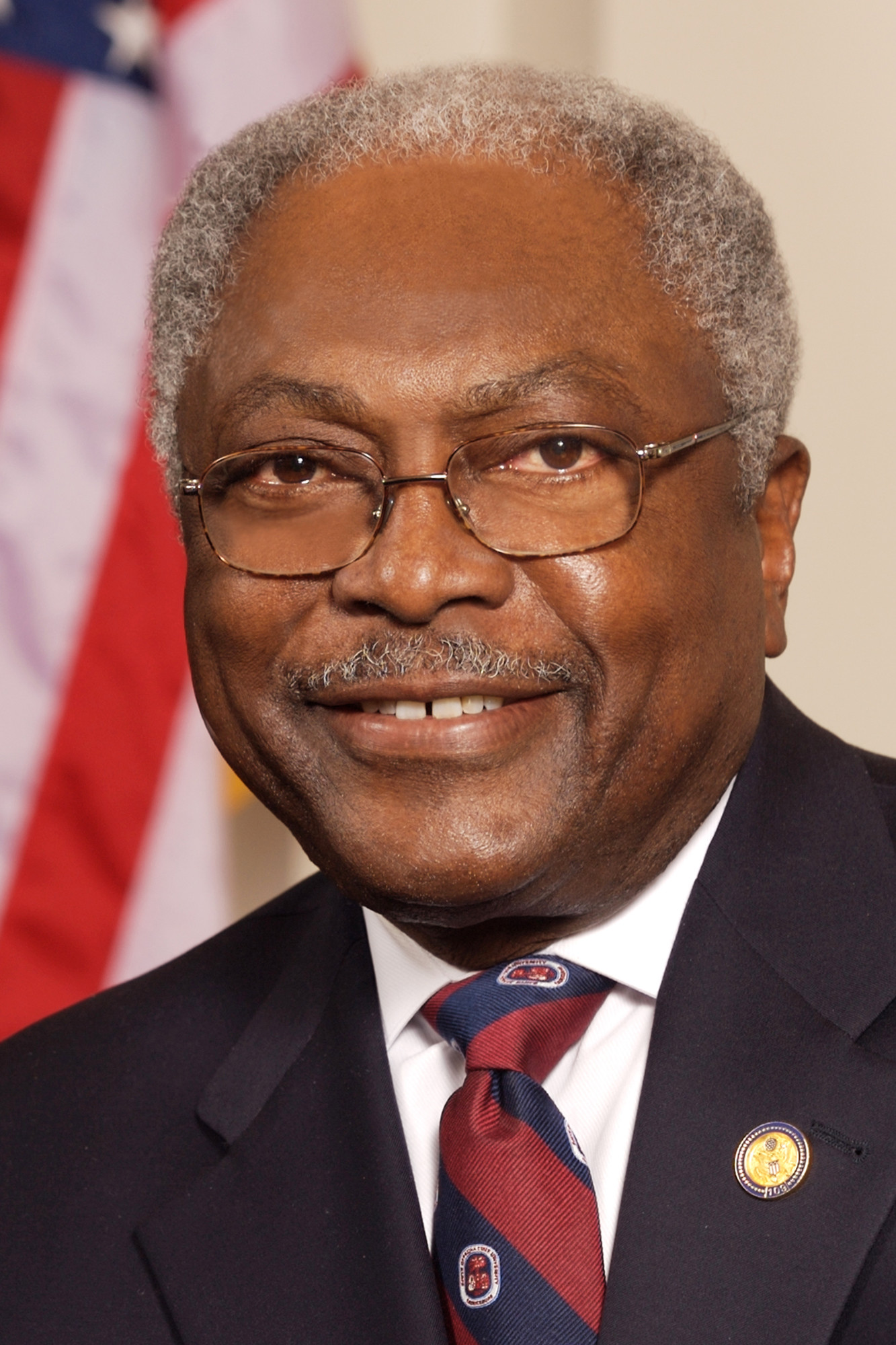

Clyburn donates congressional papers to USC

COLUMBIA — Sumter native and No. 3 House Democrat James Clyburn is sending his congressional papers to University of South Carolina to help establish a new research and education center on civil rights.

“I want this center to take a hard look at what South Carolina did for the civil rights movement, and so many people don’t know about it,” Clyburn, the first black person elected to Congress from the state since Reconstruction, told The Associated Press in a recent interview.

The 75-year-old congressman is formally announcing the donation Monday morning.

Clyburn said he thinks students and citizens demonstrating for civil liberties today will be buoyed by learning of the courage shown by the average men and women — black and white — who struggled for years to achieve equality.

He said his papers will show that his work was part of a movement and that his rise in politics stands on the contributions of many other men and women who came before him.

“What I want to see in this center is young people being motivated, learning lessons that can benefit them,” he said. “It’s important for people to know that the whole issue of civil rights, of human rights, transcends race and political persuasion.”

The university’s Center for Civil Rights History and Research is going to be able to draw from the university’s collections of more than 100 civil rights leaders, politicians and citizen activists, said Tom McNally, USC’s dean of libraries.

African-American history professor Bobby Donaldson said Clyburn’s contribution comes at a crucial time.

“We find ourselves in South Carolina at a profound juncture in terms of racial matters,” said Donaldson, referring to the deaths of the nine black churchgoers at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston and the subsequent battle concerning the removal of the Confederate flag from the Statehouse.

Last week, a group of primarily African-American students walked out of class to protest what they called inequalities for minority groups on the Columbia campus, as well as the lack of black role models in academic and university leadership roles.

Clyburn’s papers document his rise to the highest levels of congressional leadership; his work on legislation such as the 2006 reauthorization of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965; and his support during the years of labor unions, the minimum wage, Pell grants and historically black educational institutions, McNally said.

Also, the papers will cast light on the inner workings of Congress and his time as Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1999 through his rise as a leader of his party and finally, as chair of the House Democratic Caucus. When Democrats regained the House majority in 2006, Clyburn was chosen by his fellow lawmakers as House Majority Whip.

The papers include his official correspondence, legislation, speeches and photographs. Because of the large volume of papers that cover his more than two decades in Congress, they will begin to be transferred within the coming months, library officials said.

Clyburn said he hopes the center will be a catalyst for study on incidents such as the so-called “Orangeburg Massacre,” in which three black students were killed by highway patrolmen during a student protest at South Carolina State University in 1968. He also mentioned the so-called “Friendship Nine,” the nine black men who refused to pay bail money after being jailed for trespassing and breaching the peace during a sit-in Rock Hill, sparking more civil disobedience protests.

Clyburn also pointed to the story of Sara Mae Flemming, a black woman who refused to leave her seat in a “whites only” area on a Columbia bus in 1954, and was struck and injured by the bus driver when she tried to leave the bus by the front door. She filed suit, which Clyburn said lead to the desegregation of Columbia’s city bus system and was a precedent for the Montgomery Bus Boycott sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks.

“This is a story that hasn’t been told,” Clyburn said of the state’s civil rights history.

More Articles to Read