Uncovered: SC citizen watchdogs fill voids as news deserts spread across the country

This article is part of The Post and Courier's Uncovered project. To read more investigations from it, go to www.postandcourier.com/uncovered/.

jhawes@postandcourier.com

ULMER - Angel Brabham didn't follow local government much, not until late 2019 when she began helping her mom keep the books at the family's fourth-generation farm.

One seemingly random day, sitting in her office beneath a sign that read "God made a farmer," she opened the mail. A reassessment notice stared back, one of thousands landing in mailboxes across rural Allendale County.

It took a minute to grasp. In all, her family's properties had received a roughly 32 percent hike. One parcel skyrocketed 194 percent.

Was she missing something? It wasn't like Allendale's property values were soaring. A rural expanse of 9,000 people on the Georgia border, its population had dwindled in recent years, a third of its residents cast into a well of poverty. The median household income hovered around $27,000.

The phone at Connelly Farms soon jangled with calls from other hit-hard farmers.

Despite their shock, they couldn't open the local paper to see what was going on. As the county's population had waned, so went its newspapers. The Citizen-Leader shuttered in 2014, and The Allendale Sun stopped printing the following year.

Allendale County had become the state's first true "news desert."

As local newspapers shrink and shutter, so go the journalistic watchdogs who once informed communities about their public officials' actions. And where the sunshine of accountability dims, wrongdoing flourishes. The Post and Courier's year-long investigation Uncovered has found many instances of government misconduct across South Carolina.

But into any void, something rises. In the absence of robust newspapers, a different kind of watchdog is increasingly stepping up: the gadfly. Like journalists, these citizen watchdogs attend government meetings, request public records and demand answers from public officials.

Unlike journalists, their goal isn't always objectivity. Or fairness. They operate in varying tones of outrage.

Some come armed with self-interest or vendettas, others as strident partisans. Many don't employ restraint or measure. More than a few fixate on single issues. God help you if they get your email address.

Most, like Brabham, just want to improve their communities.

She wasn't born a gadfly. Her metamorphosis began when she tried to appeal the reassessments and found the county didn't have an appeals board in place. She couldn't find its budget online. No meeting minutes either. And when she called the state to get Allendale County's annual financial audit, she discovered it was almost two years overdue.

Frustrated, she attended a budget workshop. It quickly became clear that nobody on council knew how much money the county had on hand. Even the treasurer couldn't say.

Brabham left stunned. A former school guidance counselor, she was no accountant. But none of that sounded good.

She was about to discover just how bad things had become without the watchdogs watching.

Dean of gadflies

The notion of a gadfly has existed for more than 2,000 years. The Greek philosopher Socrates described himself as one, referencing the tenacious insect (think horsefly) that bites the hindquarters of a much larger beast. With piercing questions, he challenged the people of his native Athens to snap from their intellectual apathy.

"I rouse you. I persuade you. I upbraid you. I never stop lighting on each one of you, everywhere, all day long," Socrates said, according to his student Plato. In fact, Socrates irritated Athenians enough that a jury sentenced him to death, likely by drinking poison hemlock.

As millennia passed, the term stuck.

If South Carolina ever had a dean of gadflies, it was Edward "Ned" Sloan Jr. He died in 2020 after devoting a long retirement to prying public records loose and forcing public officials to adhere to their own laws.

Sloan wore a gold gadfly pin on his lapel when his lawsuits made it to the state Supreme Court. Former Chief Justice Jean Toal called him the court's "favorite gadfly."

He loved it.

Over several decades, Sloan filed more than 100 lawsuits against public officials and entities - including then-Gov. Mark Sanford, Friends of the Hunley, Clemson University and the state Legislature. Unlike most citizens, and even many newspapers today, he had the financial means to do so.

A Citadel graduate and engineer, he had run his family's road-paving business, then sold it when he retired. From his home in Greenville, he'd also watched local newspapers struggle.

"He knew that his kind of lawsuits were taking on an increased importance in the absence of investigative journalism," Sloan's longtime attorney, Jim Carpenter, said. "He decried the absence of real local reporters in local newspapers."

Sloan stepped up, spending $3 million to $4 million of his own money over the years to haul public officials to court. In 2005, he also created the South Carolina Public Interest Foundation, a non-partisan group "dedicated to ensuring that South Carolina governments and agencies act in strict compliance with the state Constitution and laws," its website says.

A common tactic among public agencies is to obstruct Freedom of Information Act requests, gambling that the average citizen or cash-strapped news outlet won't take them to court to force compliance.

Sloan basked in doing just that.

He focused on open records cases and tapped his familiarity with government contracts to bring lawsuits - and won roughly a third of them, Carpenter said.

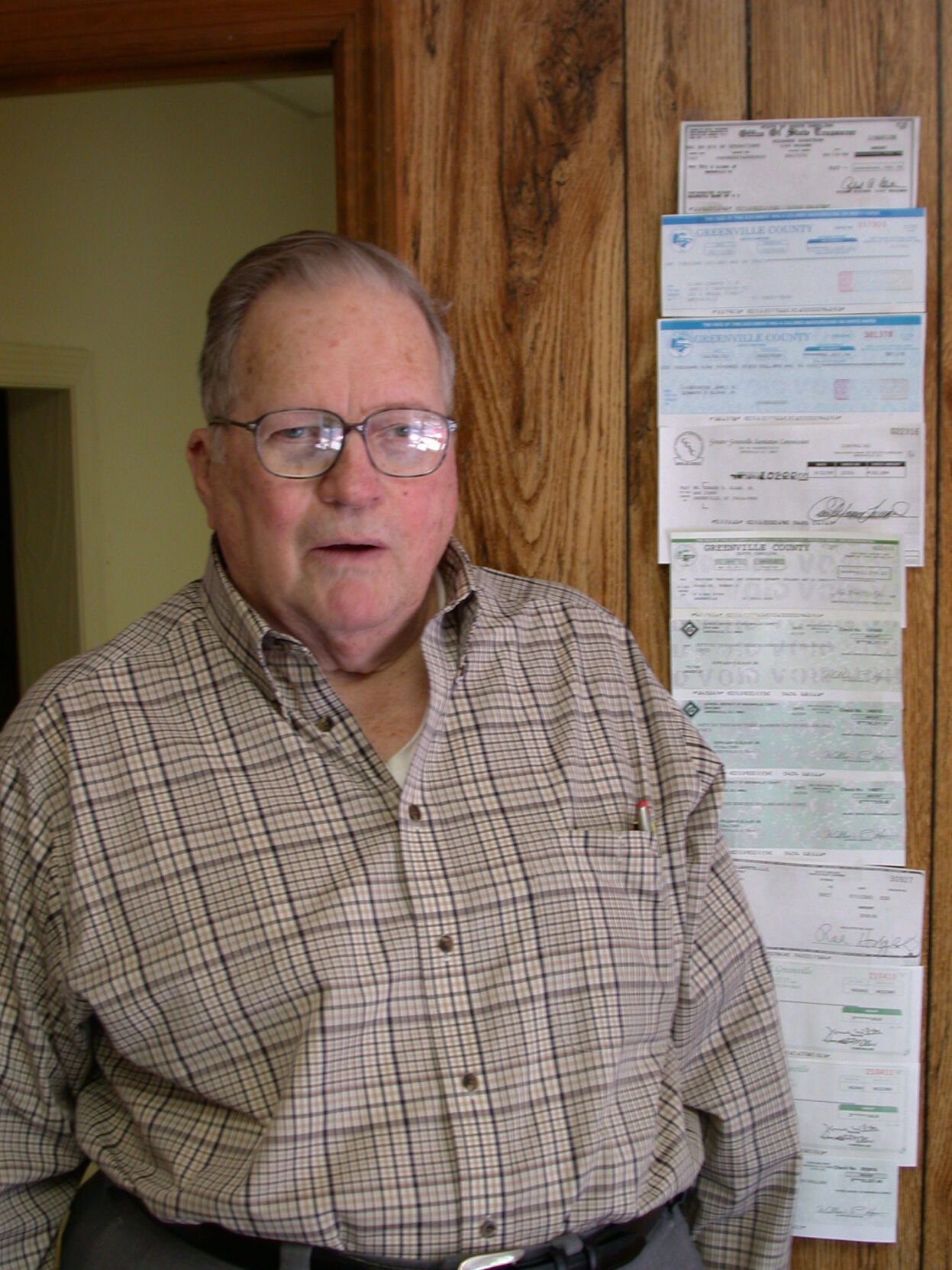

Along the way, Sloan received dozens of rulings awarding him attorneys' fees, so many that he strung together color copies of the checks and hung them in his office. One was for more than $100,000.

Yet he also wanted to set precedents, such as establishing the right for someone to bring a lawsuit, especially in cases regarding the open records law.

"Then more people could follow the path he blazed," Carpenter said.

And they have.

Small-town wrath

Back in Allendale, the more Brabham dug, the more horrified she became.

As Allendale's newspapers vanished, three of its public officials were jailed on embezzlement charges. The state took over its schools - twice. Locals began to crack that their public officials only left office in handcuffs or a casket.

But it didn't have to stay that way. This idea motivated Brabham like little else.

She began attending public meetings, along with a few other residents - but rarely a journalist. When she couldn't get answers about the county's sloppy finances, she typed up a formal Freedom of Information Act request. She wanted to see the county's most recent bank statements and records for credit cards provided to officials.

County officials didn't respond. Maybe, she thought, the law is only for journalists to use. (In fact, it is for everyone.)

Frustrated, she dashed off emails to state officials: senators, the treasurer, comptroller, attorney general, Gov. Henry McMaster - anyone with ties to state oversight or Allendale County. Brabham begged for help.

In a neighboring county, she also noticed a noisy gadfly named Walt Inabinet posting on the Facebook group Concerned Citizens of Bamberg County. A retired journalist and economic development official, he regularly fired off pointed rants railing about perceived mismanagement of county affairs by those in charge.

Brabham copied the idea, if not the tone, in fall 2020. On Concerned Citizens of Allendale County, she posted agendas, recapped meetings and politely called out public officials. More than 800 people soon followed it.

At first, many were afraid to speak up with her. Nobody wanted to hear their loved ones named as part of the problem. And in such a small community, enemies are hard to shake.

When she attended council meetings, peppering members with questions, they seemed more annoyed than openly hostile. But as they too realized the depths of their problems, most said publicly that they welcomed the renewed attention. Once, when she was 10 minutes late to a meeting, the sheriff's deputy working at the door told her that council members had just been asking where she was.

Instead, rancor flowed from outside the council chambers. When Brabham raised an ethical question about one council member's employment ties to the county, a man on the Facebook page called it "a bunch of bull (expletive)" and warned her to "leave this matter alone."

She carried a firearm more often and looked over her shoulder.

Research shows that fear of this kind of pushback keeps people from stepping up as watchdogs. A study by Rutgers University professors found that focus group participants followed the news but had almost no interest in jumping into the fray.

"The potential risks ... outweigh the benefits of making their concerns more public," the study's authors wrote.

That didn't stop Brabham. When Allendale County finally submitted its long-overdue audit, she posted it on the Facebook group. People needed to know the shameful state of the county's finances, especially the many "material weaknesses" that auditors cited.

Inabinet, the gadfly from neighboring Bamberg, commented on the post - and not in the gracious tone Brabham carefully adopted.

"The State Treasurer's Office ought to come down on the County like a ton of bricks AND SHOULD NEVER HAVE ACCEPTED THIS 'REPORT' AS A STATE-MANDATED 'AUDIT'! Allendale County folks should be shocked by the lack of financial controls and accountability...and I do mean shocked!" he wrote.

Brabham felt vindicated.

More locals openly applauded her efforts. They asked questions, including how to get involved.

Although Brabham didn't know it, her state senators also were listening. Noting emails from concerned residents, Brad Hutto and Margie Bright Matthews wrote a formal letter to the governor seeking help in Allendale.

They labeled it "urgent request."

Persistence required

Brabham didn't know it, but across South Carolina, the gadflies were multiplying. In a neighboring county, a trio of women with no connection to government felt a similar calling.

Susan Kearse Clayton grew up in Bamberg County but moved away to attend college in Georgia, then worked as a web developer and graphic designer in the Atlanta area. When she returned to Bamberg in 2015, she couldn't believe the state of her hometown.

Struggling with soaring unemployment, high taxes and persistent poverty, the county had lost about 20 percent of its population since 1980. Many of the downtown storefronts in the county seat were crumbling, empty or boarded up.

"I came back to a ghost town," she said.

She wanted to get involved but felt county officials had little interest in hearing from folks footing the tax bill. She wasn't alone.

Miriam Beard, a former Philadelphia-area child abuse investigator, had moved to Bamberg to care for her ailing father. She cared deeply about the area given that her family's lineage stretched back to before slavery's end.

Deanna Miller-Berry, a community and political activist, had arrived from Dorchester County. She soon raised alarms about environmental issues, including the lack of clean drinking water in the town of Denmark.

The three women, with others, began to pool their skills and learn all they could about the county's government - a task made more difficult when Bamberg's hometown newspaper, the Advertizer-Herald, cq folded last year.

Since 2004, the nation has lost a quarter of its newspapers. That's 70 dailies and more than 2,000 non-dailies. With them went about half the journalists who traffic in the printed word, according to "Vanishing Newspapers," a research project at the University of North Carolina.

Most of those bygone newspapers covered smaller, more isolated and struggling communities, particularly across the South. Places like Allendale and Bamberg.

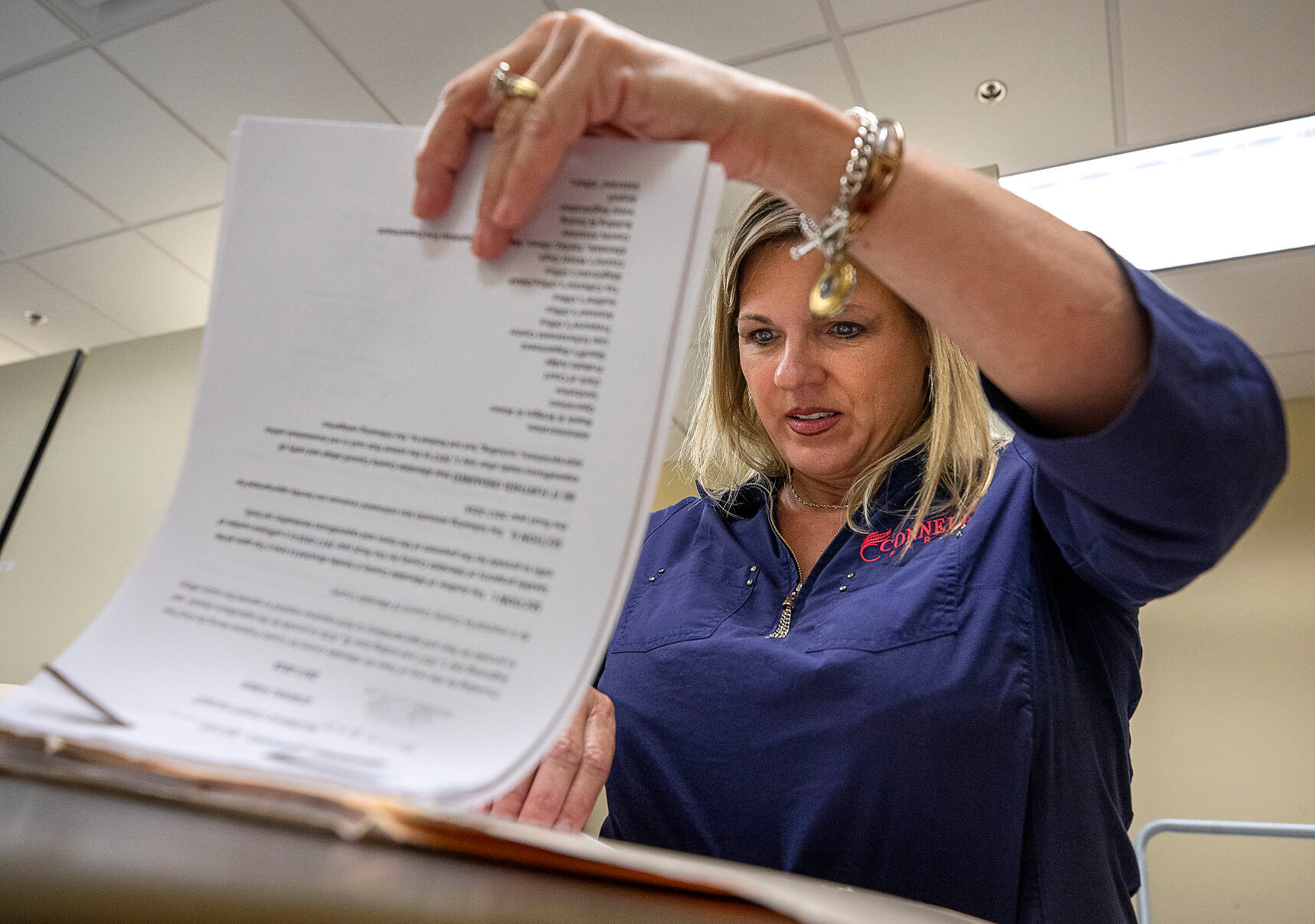

So the three women did what journalists would have done. They scoured audits, haunted meetings, and questioned how and why things were done.

They also re-invigorated the Concerned Citizens of Bamberg County, which recently launched a petition drive to force a do-over of the county budget adopted in June. The group contends that council didn't follow state law in approving the $27.5 million spending plan and that some members didn't even know what they were voting on - claims county officials strongly deny.

Those local leaders haven't made it easy, Miller-Berry said. But like journalists, most gadflies carry stock in persistence.

She pledged, "We are not going to stop until we get to the bottom of what's going on."

State of affairs

Back in Allendale, a week after the state senators sent their "urgent request" to the governor, the County Council met.

One councilman noted that they had run into a scary predicament: The county almost didn't have enough money on hand to pay employees. Officials had dipped into the county's capital reserve fund to meet payroll, and to pay $400,000 in IRS penalties, Treasurer Gerzell Chaney told them.

Members complained that Chaney hadn't given them revenue reports - not ever. They had no idea how much money the county had at any one time, and they had little power to discipline her, given she was elected to office.

"Since 2014, six years, we still haven't got a balanced account," Councilman Rick Gooding said. "That's my concern."

Soon, Chairwoman Theresa Taylor's voice rose: "Do a forensic audit. Do a forensic audit! Do a forensic audit!"

Brabham watched in shock.

When the public comment time arrived, she stood to speak. Shaken, she thanked the council. Then she presented a petition asking them to livestream or record their meetings for residents who could not attend them.

People needed to see what was going on.

'Lots of places to dig'

When Fordham University journalism professor Beth Knobel began researching newspaper accountability coverage, she knew the prevailing wisdom: Newspapers were operating with smaller staffs, often under severe financial stress, so the watchdog role was getting cast to the boneyard.

"Actually, all my research suggests the opposite," she told The Post and Courier. "Local newspapers are more committed than ever to serving the watchdog role."

She had examined coverage in nine newspapers and found "there was more digging than ever before."

So the issue wasn't interest. It was capacity.

That's one reason the line between journalist and gadfly has thinned in recent years. As newsrooms shrink, some news organizations are seeking help from the general public to fulfill their watchdog duties.

Some train gadflies to gather information, although that cannot replace a reporters' more in-depth understanding of things like journalism ethics and libel law.

In Chicago, the nonprofit journalism lab City Bureau is training hundreds of citizens to attend public meetings. These attendees then post their findings on platforms like Twitter and the nonprofit's web app, Documenters.org.

The Documenters project has spread from Chicago to Detroit to Cleveland - with more cities coming. (A co-founder told The Post and Courier that they've received interest from Atlanta and North Carolina, but so far not South Carolina.)

Meanwhile, the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism has launched a page that trains gadflies with Watchdog 101 workshops and primers on everything from using the state's open records law to backgrounding people. It is modeled after an initiative in Maine.

"Citizen journalists add a new layer," Knobel said. "Newspapers only have so many people to dig. And there are lots of places to dig."

Doing the homework

One place in need of digging is the small town of Chester, tucked off Interstate 77 between Columbia and Charlotte.

Nettie Archie grew up there, then moved away after graduating high school in 1963. The textile town was on the rise with railroads, a bus station and a busy downtown. But when she moved back 20 years later, she found her hometown in decay. Growth that once seemed destined for Chester instead headed 20 miles northeast to Rock Hill.

Her research pointed to a key reason: government corruption and incompetence.

"Going back 25, 30 years ago, corruption has always been here," Archie said. "It was on a smaller scale. But now, it's just all over the place. It seems as though people feel they can get away with more."

In recent years alone, Chester's county sheriff was convicted of public corruption and abusing his power. Its supervisor was indicted on charges of selling meth out of his county vehicle. And a county judge was suspended for failing to recuse herself from cases brought by her husband - the aforementioned sheriff.

Archie, a 76-year-old businesswoman, decided to dedicate her life to calling out wrongdoing. Her brand of polite-but-stern activism has made an impact in this town of 5,300.

In the mid-1990s, she landed on the front page of The Chester News and Reporter when she stood up at a County Council meeting and asked detailed questions about the budget they were about to pass. When embarrassed council members couldn't answer her questions, they postponed the vote and restarted the budget process.

"They looked so bad," Archie said with a laugh.

Like gadflies across the state, she badgered local councils to make their meetings more accessible to the public, such as holding them at times when everyday citizens can attend.

In 2018, she challenged the legality of Chester City Council's chaotic vote to hire a new city administrator. That same year, she flagged neighbors' complaints that the city had caused a vermin infestation by turning its Public Works department into a temporary trash dump. At Archie's request, a Charlotte news station flew a helicopter to photograph the piles of waste.

She also linked up with another local activist, Jeremy Clark, to form Chester Citizens for Ethical Government, a watchdog group that seeks to expose government wrongdoing.

A month later, the group filed a lawsuit seeking to remove Chester City Councilman William King from office, arguing his status as a convicted felon should have barred him from seeking election in the first place. A judge tossed the councilman from his post.

In 2020, she helped lead the successful campaign to defeat the school board's $116.5 million bond referendum, contending the district hadn't laid out clear plans for the money.

But not everyone likes the group's tactics. Local officials call it a band of bullies who weaponize rumors to harass public officials.

"I grew up respecting her," Chester City Councilwoman Angela Douglas said. "But once she connected with some organizations in Chester, I saw a change in her behavior. I saw an aggressiveness."

Archie denied being a bully.

"When I call them out on something, trust me, I've done the homework," she said. "No, I'm not being vindictive. You're just not doing the job you've been elected for."

Moving forward, Archie issued a warning: she will be monitoring how city leaders spend the $2 million in coronavirus relief funding they are set to receive from the American Rescue Plan.

Shining light

Back in Allendale County, Brabham exhaled when council members finally hired a forensic auditor.

When the auditor's report arrived in late June, the council scheduled an emergency meeting. Wearing a hot pink T-shirt that read "love more," Brabham left the family farm and steered her white Lincoln to the courthouse, anxious. Dark clouds clustered in the sky.

In the meeting room, she sat in back near a camera livestreaming it for residents everywhere to watch. For once, Brabham didn't plan to speak.

A reporter from the Barnwell newspaper was sitting in front of her. The reporter turned around to ask, "Are you the woman who runs the Facebook page?"

When a council clerk walked around handing out copies of the audit, a half-dozen people in the audience reached for copies.

Ronald Burkett, whose firm conducted the audit, soon began by explaining that a general ledger is the most fundamental of accounting tools - but the county didn't even have that. What they did have "makes absolutely no sense," he said.

Burkett outlined the county's lack of invoices, missing payroll records, bonuses the county clerk paid to employees but didn't report on payroll or W-2s, the sheriff taking out cash withdrawals without explanation of the money's use. Records were hard to find or flat-out missing. The rural county had 45 bank accounts, some taken out in individuals' names.

"The records were in a mess," he said.

Burkett noted that accounting procedures can't stop people from trying to steal money - but they can make sure someone detects it. Allendale County lacked those basic checks and balances.

In a strange way, as she listened, Brabham felt a burden lift. The county had a new treasurer, and the council members and administrator were voicing eagerness to fix the problems. And at least now the public knew what was going on.

When she stepped outside, her head still spun. Allendale's problems were huge, and so much work remained. But as she drove home, she noticed that the storm had cleared, and sunshine lit the road ahead.

Glenn Smith contributed reporting from Charleston, and Avery Wilks from Columbia.

More Articles to Read