Opinion: 'Personal recollections, experiences of journalism in this state for the last half century - 1906'

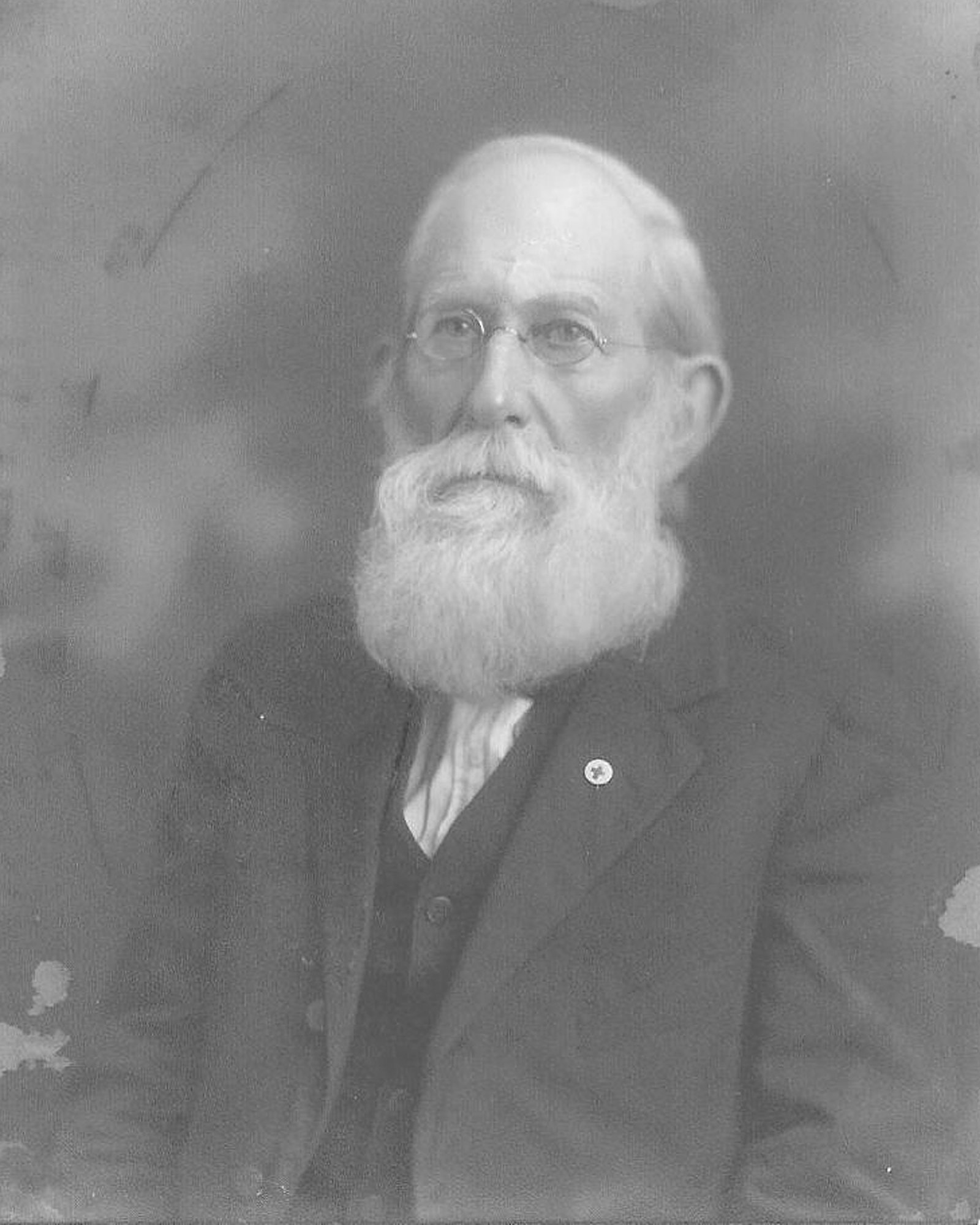

Editor's note: This address was delivered to the South Carolina Press Association on July 18, 1906. Noah Graham Osteen (1843-1936) was at the time the 63-year-old publisher of The Watchman and Southron in Sumter, a weekly newspaper that ceased publication upon his death in 1936. The Sumter Item was founded by his son, Hubert Graham Osteen, 12 years earlier, in 1894. In addition to publishing The Watchman and Southron, Noah was a regular contributor to The Sumter Item up until his death from complications that occurred after being struck by a car while riding his bicycle in downtown Sumter. Today, six generations of the Osteen family have been involved in community journalism, dating back to Noah's beginnings as an apprentice printer in 1855.

- - -

Mr. President and members of the South Carolina Press Association:

What I may be able to give you as my “Personal Recollections and Experiences of Journalism in this State for the Last Half Century” will be necessarily more local than general and will, I fear, draw too much on the “Cap I” to hold the attention of all of you throughout.

My personal recollection of journalism dates from a time when, as a country child, I began to read the Black River Watchman, to which my father subscribed, and which was started in April 1850 by A.A. Gilbert and John F. DeLorme, printers, with the late Judge T.B. Fraser and his brother, L.L. Fraser, editors.

Sumter was then a village of 1,000 or less population with no railroad and was called Sumterville. T.B. and L.L. Fraser were also associated together at that time as lawyers.

There was also another paper published there, called the Sumter Banner. It was printed by W.J. Francis, but who the editor was I do not know.

I presume that the papers had a hard time to get along, for the Black River Watchman changed hands several times in the next few years, and so did the Banner. About 1854 or 1855 the Banner, having been bought by Mr. John S. Richardson, and Mr. Gilbert having obtained control of the Black River Watchman, the papers were consolidated and the name changed to the Sumter Watchman, with Gilbert and Richardson, editors and proprietors, and John R. Haynesworth, associate editor.

About this time, the Wilmington and Manchester Railroad was built, and Sumterville changed its charter to a town and dropped off the “ville.”

Occasionally when I came to town I visited the printing office sight-seeing and got it into my head to be a printer. In the latter part of 1855, when I was less than 13 years old, I read in the paper that two boys were wanted to learn the printer’s trade and that boys from the country would be preferred. I talked the matter over with my father, and he carried me to town to secure one of the places. Being small for my age, there was some objection to me on that account, but Mr. Gilbert took me on trial, and I afterwards entered a five-year apprenticeship – serving altogether nearly five-and-a-half years.

Soon after commencing on trial with Gilbert and Richardson, another partner was added in the person of Mr. H.L. Darr, a practical printer from Charleston, but he soon bought out Mr. Richardson, so that I served my apprenticeship with Gilbert and Darr. Mr. Haynesworth having retired from the editorial staff, Mr. Gilbert was sole editor, while Mr. Darr directed the work of the office. They were both good printers and fast typesetters, Mr. Darr being classed as a “swift.” But they were not alike in any respect, Mr. Gilbert being full height, dark complexion, a full head of black hair and with an impediment in his speech, and quiet, to reserve in manner, while Mr. Darr was inclined to be short, what hair he had was red, a florid complexion, a sky blue eye that never rested but was continually moving from side to side, a free talker and inclined to be jovial in disposition.

He was quick in all his movements and so full of energy that he was always trying to keep the work ahead. He was miserable if he could not get the paper out ahead of time; at first, he would have the forms ready the evening before, so the press work could start early the next morning, but he would gain a little each week until the form would be ready so early in the afternoon that he insisted on printing the paper a day ahead of the date. Before long, it was the custom to go to press early in the morning of the day before the date, and then he kept on getting ahead until he went to press Wednesday morning for a Thursday dated paper. Then, to even up, the date was changed to Wednesday, but he would soon have the forms closed up on Monday.

He was full of energy and put all of it in whatever he went at. While he was quick and sometimes irritable, I liked him best of the two, and when he married and went to housekeeping about a year after my apprenticeship began, I asked to change my home from Mr. Gilbert’s house to his, which he agreed to and built a room for me. Other boys were taken into the office, and during most of my time there were four of us and only one man. The man being necessary to pull the Washington hand press on which the paper was printed and a smaller one on which all jobs were done, from a wedding invitation to a horse poster. So far as I know, hand presses were at that time used by every paper in the state outside Columbia and Charleston, excepting, perhaps, the Yorkville Enquirer, which was one of the first country papers to use power press.

It was the custom in those days for every printing office to make its rollers, and I had much personal experience in that line during the years of my apprenticeship and for several years after. It was usually an all-day job, in fact longer. The glue was put to soak overnight and put to melt early in the morning. When melted, molasses was added and the mixture boiled until the water was expelled and the composition of the proper temper. The mold in the meantime having been cleaned thoroughly and oiled, the composition was poured and left to stand all night before drawing. Sometimes the roller would be too soft and another trial necessary. If the oiling of the mold was not just right the roller would be spoiled, sometimes from too much oil, making defects in the surface, and sometimes from being too little oil the roller would stick in the mold and be very difficult to get out.

I recollect that on one occasion we were trying to get a roller out of the mold, and after failing to push it out Mr. Darr set the planer endwise on the floor and put the mold over it with the end of the roller stock resting on the planer. He then got on one side and I on the other to pull down on the mold and force the roller up. I swung with all my weight and in trying to make my weight give a little more gave an extra jerk; this tilted the planer, and the mold came down on Mr. Darr’s big toe.

We finally got the roller out, but he was not able to walk to the office for several days. The making of the printers’ rollers is now a specialty, and we can get better rollers on short notice than we can make, and at prices less than the material and time to make them are worth. The difficulty to get rollers 50 years ago was, no doubt, largely the reason for the bad printing of most country offices – a well-printed paper being the exception; but the rollers alone were not always the trouble.

I have seen papers come to the office that were so wet they could hardly be handled without tearing, it being the custom then to dampen the papers before printing, and some with such poor ink that it would rub off on anything that the paper touched. There were, however, some well-printed papers that I always enjoyed looking at when a boy, and I usually spent some of my leisure after-working hours in looking over the exchanges.

One of those papers was the Yorkville Enquirer, and it is the only one that I now think of that still looks almost the same that it did then, except some difference in its size. It was the fashion in those days for paper to be printed in much larger format than now. Most of the papers that came to the office then have ceased to exist or have changed ownership or title.

Among the papers I knew were the Pendleton Messenger, then over 50 years old; the Camden Journal, also up in years; the Edgefield Advertiser, the Greenville Enterprise, the Barnwell Sentinel, the Columbia Banner. Of the six, only two now exist, and the changed geography of the state would render the names of some of them inappropriate now even were they still printed.

Coming back to where I started – journalism in Sumter – Mr. Francis, who had owned and sold the Banner, decided to re-enter the field, and about 1858 he and Mr. Charles H. DeLorme started a paper called the Sumter Dispatch, which ran for two or three years, when it was bought out and killed by Gilbert and Darr. The starting of the Dispatch roused Gilbert and Darr to the necessity of hustling, with the result that they made the Watchman a tri-weekly.

There was no telegraph office in Sumter then, not even for a railroad service, and the paper depended on clipping the daily papers for news. Submarine telegraphy had not been accomplished, and the metropolitan papers got their foreign news by steamer and headed the news columns with the cut of a steamship (side wheeler) and with the name of the ship bringing in the mail, in heavy type under the picture. The usual time of a steamer from Liverpool in those days was nine to 11 days.

The Tri-Weekly Watchman did not, for reasons stated, deal in specials, but it had a steamship cut and devoted some space to foreign news clipped from the Wilmington Journal or Richmond Dispatch, which papers reached us on the train arriving about 4 a.m. and usually contained later news than could be gotten from the Charleston or Columbia papers, which arrived too late in the evening to be used before next morning.

The paper lived until April 1865, when Gen. Potter’s raid passed through Sumter and knocked the office into disorder.

I was not there when that happened and therefore have not “personal experiences or recollections” of the occurrence. My apprenticeship had ended in the early part of 1861, just after the taking over of the Dispatch by Gilbert and Darr, who, in order to dispose of the surplus material, started a paper at Conwayboro (now called Conway), and I was employed by them to run it. They used the same head by putting Horry in place of Sumter, and that was the first paper ever published in Horry County.

At first, I had two hands (my former fellow apprentices) to assist me in getting out the papers, but at the end of the year the proprietors decided to cut the paper to a half sheet - that being the form that most of the county papers were published in during the war - and I was offered the job of getting it out by myself, which I did until the publication was suspended in August 1862. Mr. Joseph T. Walsh, then a lawyer in Conwayboro, and afterwards judge of the county court, was the editor, while I was business manager and everything else. I did some hard work and had considerable to worry about, but on the whole I had a good time and have many pleasant recollections of my stay in Conwayboro.

I was hardly more than a boy when I went there - just past 18 - and had much to learn. Mr. Walsh was very kind to me, and besides helping me with the mailing on publication nights, took a fatherly interest in me generally. He was a man of strong character, plain and straightforward in manner, and at the same time kind and thoughtful in his bearing toward me. A true man and a perfect gentleman. I have always since felt that it was good for me that I met him when I did, just as I started out in life, and that the influence of his character followed me long after we parted.

Upon leaving Conwayboro, I had an offer in Wilmington but decided to go to Columbia, where printers were in demand. I first took a job in the office of the Guardian, owned and edited by C.P. Pelham, A.T. Cavis being the foreman, and Washington Davis being in charge of the job work. After staying there a short time, I changed over to the Carolinian office, then owned by Dr. R.W. Gibbes, with Julian A. Selby, foreman.

Next door to the Carolinian office was the large lithograph printing establishment of Col. Blanton Duncan, where Confederate money was being printed for the Confederate States treasury department. Inducements were offered for printers to learn that work, and some of my acquaintances being employed there, I decided to change my line. Got a job there and remained until after Col. Duncan lost his contract, and as the shop was doing very little then, I went back to the Carolinian office, which in the meantime had changed hands, having been bought by Felix G. DeFontaine (then better known as “Personne,” a war correspondent of the Charleston Courier) and some others.

Henry Timrod, the poet, was also connected with the paper as one of the editors and, as I then understood, proprietors; but I do not know if he was proprietor or employee. He was a quiet, easygoing man who did not have much to say when I saw him about the office and did not assume much, if any, authority.

On the contrary, Mr. DeFontaine seemed to be bustling around generally and was apparently the man of authority.

I was told that the real owners, or the parties that put up the money, were George A. Trenholm and Theodore Wagner of Charleston. This I believed to be true because I saw Mr. Wagner about the office afterwards and heard Mr. DeFontaine speak of him in connection with the business.

I had been holding a case on the Carolinian for some time before the coming of Sherman’s army, but my acquaintance with Mr. DeFontaine was only that of an employee up to that time.

He succeeded in getting his type, presses and paper on the cars away from Columbia before Sherman arrived. How it was done I never knew, for I was ordered out with Col. Thomas’ regiment of reserves and kept on duty for two days and nights until the small hours of the Friday morning on which Columbia was surrendered.

On being disbanded and told that the city would be surrendered at 9 o’clock, not knowing what else to do after going to my boarding place and finding it deserted, I went to the depot in company with a friend and got on the last train that left Columbia going toward Charlotte. We did not get to Chester until Saturday night, where I got off and spent the night. Next day I found Mr. Fontaine there with two of his printers, W.H. Wilson and J.W. Gray. He decided to unload his material there, and we spent the day and the next morning hauling it uptown and storing it.

On Monday night, he got alarmed at reports of the approach of the enemy, and we all got on a train that had a lot of his material still aboard and started for Charlotte, where we arrived next day.

He made arrangements to print his paper in the office of one of the Charlotte papers and did so for a short time. During most of the time I was laid up with measles, to which I was exposed in the train on which I left Columbia. I recovered in time to assist in getting out one or two issues before he decided to move back to Chester, where we opened up in the office of the Chester Standard, owned by George Pither, but then, like many other papers in the state, suspended.

At Chester, we were joined by two more of the old office force from Columbia, Mr. William Dean and a mute named Nichols. Our force had been increased in Charlotte by A.F. Pendleton, of Augusta, Georgia, and a Mr. Ackerly. Wilson was a foreman and Pendleton pressman. An Adams book press was all we had to print the paper on, the frame of the Hoe cylinder having been broken when it was unloaded from the car. We printed a paper in Chester a short time only.

Soon after the surrender, toward the latter part of April, Mr. DeFontaine decided that he would suspend until about October, when we would move his material to Charleston and resume publication of the paper. In the meantime, Mr. Selby had started a paper in Columbia and called it the Phoenix.

It was a very small affair at first, being printed on a proof press - a long strip about three columns wide. But he scoured the country around for material and soon got together an outfit to get out a fairly good paper and do job work. I heard that he charged high for what he did and made money. We disbanded and went to our homes, and Mr. DeFontaine went north and did a fine business soliciting advertisements to be put in his paper when started.

I do not remember now whether we got any wages or how we managed during all that moving around. We slept in the office or place the material was stored, and part of the time Mr. DeFontaine sent us meals from what he had for himself and family. He had his wife and one child, a little girl, and one or two servants. His wife was a Miss Moore, daughter of a Methodist minister, and they made themselves at home at the Methodist parsonage in Chester and at Charlotte. I recollect that in one end of the box car in which we went to Charlotte was a pile of bacon across the whole end of the car, and when we arrived there and were about to disembark, Gray (the printer) insisted upon taking a shoulder of the meat.

I objected, thinking it belonged to some family, but he had his way and put it in a long pillow case that seemed to go with the servant’s things. After he got it out, I helped to see that it did not get lost, and I was afterwards very glad we had it, for I think we would have suffered if we had not had it.

When we left Chester we rode on the train to Blackstock, about 12 miles, where the road stopped, Sherman’s army having destroyed the road from Columbia up to that place. From there we walked to Columbia, and from Columbia I traveled with some wagons that were coming to Sumter but had to walk most of the way.

After spending the summer on the farm in the country, I was notified in October by Mr. DeFontaine that he desired me to meet him in Chester and assist in moving his office to Charleston. The railroad had not been repaired to Columbia on either side, Hopkins Station, about 12 miles from Columbia, being one end of the road on the Charleston side and Winnsboro being the last station on the Charlotte Road.

We had about six four-horse teams, secured in the vicinity of Winnsboro, with which we hauled the stuff through Columbia to Hopkins’ Station.

The trip, including loading and unloading, took two days, besides one night spent in camp on the way, and we go away from Hopkins the second evening and arrived at Charleston about daylight next morning. There was a wearisome delay, however, before we got the stuff from the railroad and the plant straightened out. We finally got everything together in a building on Hayne Street, I think it was No. 18, and began to get the paper out. The Daily News was very near, perhaps next door, and the Courier across the street, near Meeting.

Mr. DeFontaine had a strong staff of writers. I cannot name all, but besides letters from Mr. Timrod who was in Columbia, or somewhere in the upcountry. He had the well-known novelist William G. Sims, B.R. Riordan and a Mr. Thomas, quite a literary man, who said he had been a private secretary to President Tyler, and a great friend to the president’s son, Bob, and Bob’s wife; also Tom Corvin, a noted politician of Ohio.

Bob Tyler’s wife, he said, had been an actress, and it was through her influence after she became the First Lady of the White House that he received his position. He had been a reporter before then and had written up her performances so acceptably to her that she did not forget it. He had a short leg and wore a shoe with a stick about eight inches long attached under the shoe. Besides these, there were other reporters, all of whom I did know.

Mr. De Fontaine had very little money, and his backing had weakened so that with the expensive paper that he was trying to run he was soon very hard up against it, and by spring he concluded it would be cheaper to run a paper in Columbia and that he would move back there. In the meantime, I had married and could no longer afford to follow him the way matters looked.

I did not stay until he broke up but moved my family to Sumter then, intending to join him in Columbia after fixing them there; but circumstances changed, his paper did not last very long in Columbia, and in the fall I bought an interest in a newspaper lately started in Sumter by my old instructor, Mr. Darr. The paper was first called the News, but we afterwards changed its name to the True Southron. This was at the time that radical and scalawag influence was dominant, and the papers of the state were largely following the lead of some politicians who advocated joining what they claimed to be the best part of the Republican element, white and black, in order to get into power.

I had many experiences and recollect much of the 16 years of my co-partnership with Mr. Darr, in which we went through the days of Reconstruction, etc., and also of the 25 years since Mr. Darr and I dissolved partnership, but I cannot trespass further on your endurance and must cut this short.

In mentioning the staff that Mr. DeFontaine had on the Carolinian, I omitted to mention Mr. Roswell T. Logan, who came some time after we had started and was engaged in local reporting. He wrote with a quick and ready pen and had the knack of getting the meat without much apparent effort. I always liked him, and the acquaintance begun was kept up.

I seldom went to the city without seeing him, and although my calls were frequently at busy times, he was always glad to see me. He was an able man in his line and carried a big heart in his small body. The memory of him will not fade from me while I remain behind him.

Perhaps I should have also followed Mr. DeFontaine a little further. After leaving Columbia, he returned to Charleston and published for a while a magazine called XIXth Century, after which he went to New York and held for a number of years, and so far as I know, until his death a few years ago, a good position on the New York Herald.

I am also told that it was as correspondent for that paper he first came to Charleston to report the National Democratic Convention which broke up in a row shortly before the war. He married a Charleston woman, and they remained south.

He was a small man with deep, brown eyes and dark brown hair and beard, when I first knew him. His manners were pleasing, and when he smiled I thought his face handsome. He was a charming conversationalist and a brilliant and fluent writer. Unfortunately he was not a good manager or could not get the means to run a business to correspond with his ideas.

All in all, he was a good man, and I have never regretted knowing him and working for and with him as I did.

Before closing, I will mention that the late John A. Moroso, whose newspaper work on The News and Courier made him a reputation throughout the state, began as a Charleston correspondent for the Sumter News, at the time he was a student in the Charleson College, and he afterwards said that was the first writing job he did for a newspaper.

I thank you for your attention.

More Articles to Read