Some sheriffs say fixing DNA backlog will cost taxpayers more

The State

For years, every law enforcement agency in South Carolina sent DNA evidence to be tested in one place — the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division on Broad River Road in Columbia. And as technology improved, agencies started sending more and more evidence.

Now, more than 8,000 cases have piled up, waiting to be tested, according to data collected earlier this year. The exact number of cases is unclear, as they open and close daily.

SLED’s forensic analysts are stretched thin, and thousands of criminal cases have DNA evidence that has waited years to be tested, potentially delaying justice for victims and allowing criminals to roam free.

“It’s just not humanly possible for (SLED) to do that,” said Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott, who became the first sheriff in South Carolina to open an in-house forensic laboratory.

Some sheriffs think they have found a solution: Share the workload.

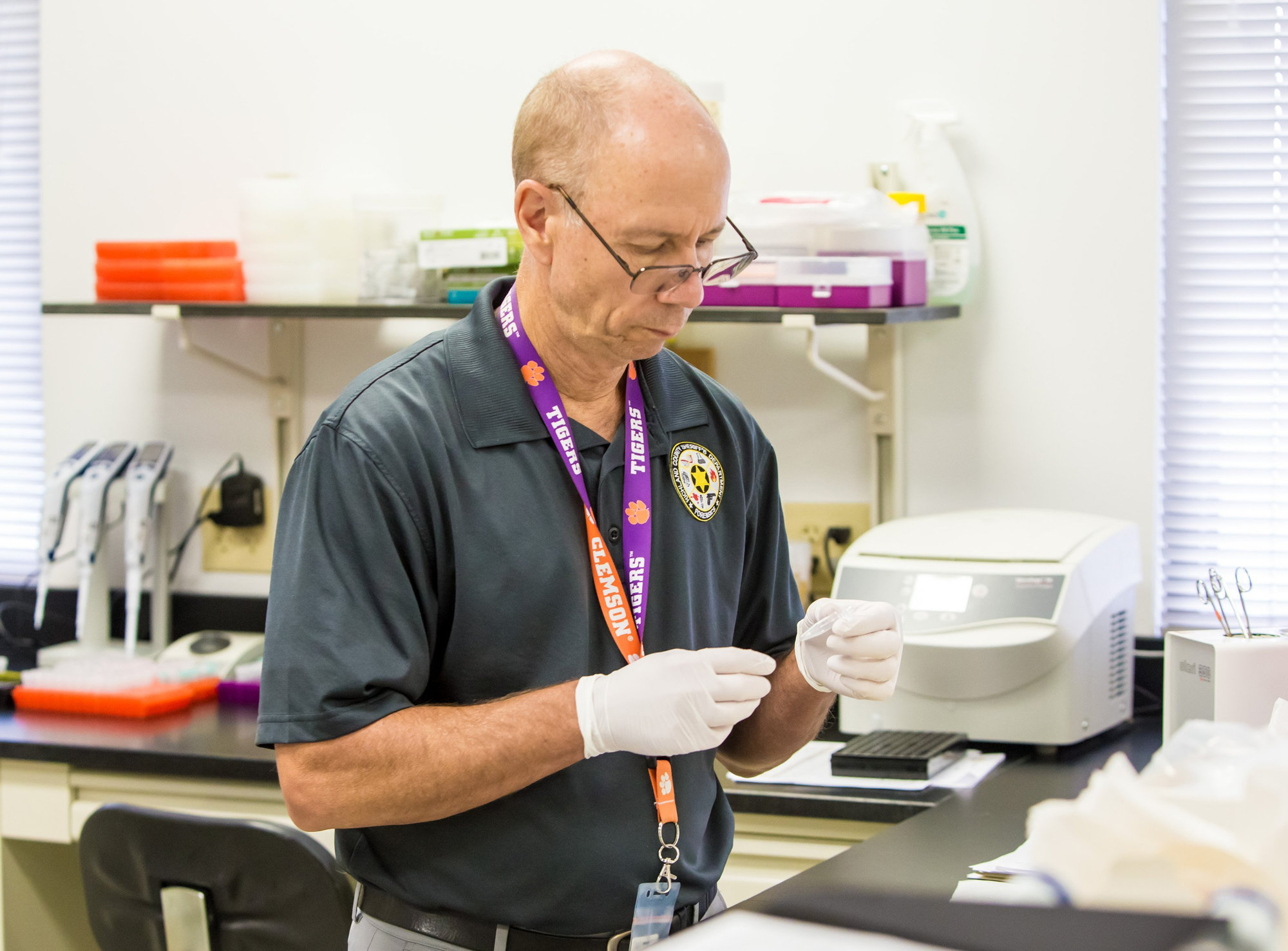

Four law enforcement agencies — Richland, Greenville, York and Beaufort counties — use their own crime lab, built with money from grants or local taxpayers, and they already help neighboring jurisdictions with their cases. That keeps cases off the state crime lab’s backlog and gives agencies their results in weeks, rather than months or years, potentially preventing further crime.

“Every case they work locally helps,” SLED Chief Mark Keel said. “You can’t deny that. That’s beneficial to us and beneficial to our laboratory.”

But to really put a dent in the statewide backlog, some sheriffs say they need help from state lawmakers.

“Richland County taxpayers are not going to pay for (processing DNA in) rape cases in Charleston,” said Lott, who passes on the cost of testing to the requesting agency.

Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office only charges the requesting agency if it has grant money to spend, Sheriff P.J. Tanner said. Otherwise, Beaufort County helps where it can, but it can only do so much.

“If we’re not sending these cases to the state for analysis and we’re absorbing the responsibilities of three, four or five counties, I think the General Assembly needs to make sure those regional labs are being funded by the state,” said Tanner, whose agency opened its own DNA lab in 2008.

The S.C. General Assembly just last year gave SLED $54 million to build a new crime lab, which was intended to improve efficiency and allow for the hire of more scientists, ultimately reducing the workload.

That leaves lawmakers like state Rep. Eddie Tallon, R-Spartanburg, scratching their heads.

“If other labs want to help their neighbors, that’s fine,” he said. But if the S.C. General Assembly gave money to any one of those labs to help the region, less money would be available for SLED to do its job for the state, he added.

“I’m not for taking any more money away from the State Law Enforcement Division,” said Tallon, a former SLED agent. “The issue is, where is the money coming from?”

Not all sheriffs like the idea, anyway.

“I didn’t want to see what’s happening today, labs springing up out of sheriff’s offices,” said Greenville County Sheriff Johnny ‘Mack’ Brown, whose agency leans on the crime lab run by the county. “There should be one central lab, and that’s SLED.”

‘THESE BELONG TO VICTIMS’

SLED doesn’t charge police agencies for forensic analysis. It’s also the only agency with a full-service lab, including toxicology and questionable documents, which studies the inks and papers for authentication.

But right now, the state’s DNA lab is splitting at the seams. Just under 10 new cases are submitted every day, more than 3,500 every year, forcing the lab to commandeer all available space on three floors in two buildings, Keel said.

It also forces SLED to limit the type of cases it handles to only those that pose a threat to public safety and the number of items it tests to five. But the law enforcement agencies don’t always follow those guidelines, said Maj. Todd Hughey, director of forensic services at SLED.

“Because of the success DNA labs are having around the nation, agencies are wanting us to test more (evidence),” Hughey said.

Agencies know they can make a phone call and ask for a rush job, and SLED will prioritize, Hughey added. One month, analysts tested 80 items from one homicide.

And each step in the process is complex and time consuming. Analysts are looking for a molecule found inside a person’s cells. They “disrupt the cells so that the nuclear DNA matter will spill out,” Hughey said, creating what’s known as a “mess.” Analysts then must isolate that DNA away from all other cellular components and determine whether there is enough to work with, and then interpret the results.

This isn’t what TV shows make it out to be, Hughey said. It’s a very long, complex process.

“Our DNA analysts are giving each one of these cases a unique, dynamic approach,” Hughey said. “It’s not samples that are coming in on a conveyor belt. These belong to victims. They belong to potential suspects in a crime. And none of these cases are the same, so we have to give it time.”

And data shows SLED’s DNA analysts are above the national average when it comes to efficiency, he added. A typical DNA analyst can work 110 cases per year — the average SLED analyst completes 157.

“Our lab is very efficient,” Hughey said. “Even though we have the backlogs that we talk about, the way we manage our resources, our funding, our staff, we’re able to give a good return on the investment the state is making.”

Still, some say more could be done.

“If we’re taking those responsibilities from the state and reducing their workload,” said Tanner, the Beaufort County sheriff, “then there needs to be some monies earmarked (by state lawmakers).”

‘IT’S LIKE CHRISTMAS’

The regional approach offers something SLED can’t — real-time information, Tanner said.

Lab technicians in Beaufort, Richland, Greenville and York counties help investigators eliminate or include suspects much faster than SLED can. They guide detectives through the investigation.

“Let’s make good cases from start to finish,” Tanner said, “and not just wait for evidence to be tested after a case is made.”

Juries are expected to make incredibly tough decisions, Tanner said, and they want to see DNA evidence. The credibility of a law enforcement officer just isn’t what it used to be, he added.

“When you can back that testimony up with scientific fact, it’s an easier job for the solicitor’s office to prosecute, and it’s an easier decision for a juror,” Tanner said.

Juries wouldn’t sympathize with red tape associated with waiting on another agency to test DNA or not being able to test certain pieces of evidence because a limit was reached.

“Unless you’ve served as a juror, I don’t think a lot of people understand how difficult that job is,” Tanner said. “They can find guilt or innocence, but they’re also dealing with the reality that if they find the person guilty, they will go to prison for an undetermined amount of time.”

On the other hand, at least one sheriff thinks it should remain SLED’s responsibility to test the state’s DNA evidence.

Brown, the Greenville County sheriff, said he is very pleased with the work his local lab does, but he’s concerned about policy and procedure across the state. One agency should be responsible for it all so everything is streamlined, he said.

“(SLED is) the state agency that gets the money to buy the equipment that labs need, and sometimes we can’t get equipment without begging, borrowing and stealing,” Brown said.

It’d be “impossible” to get the S.C. General Assembly to support regional labs anyway, he said. It’d be an easier sell to divide the state in half and build one crime lab in Greenville and another in Charleston, sharing the workload.

But work at the regional level has likely prevented more people from being victimized, said Lott, the Richland County sheriff.

Lott said the Richland County Sheriff’s Department is the only agency in the state that owns a Rapid Hit DNA machine, which cuts the wait time for DNA test results to 90 minutes.

“It’s like Christmas (for investigators) when the results come out,” Lott said. “Their cases get solved.”

More of that is possible across the state, if only these county sheriffs have the help they need.

“Thank goodness we have our own lab here, and that’s not to take anything away from SLED,” said Tanner, the Beaufort County sheriff. “They just can’t keep pace with what we’re doing here locally.”

More Articles to Read