Stephen Chesley and the marriage of science and art

"Egret, Beaufort" is one of many paintings by Stephen Chesley that are on exhibit through April 19 at Sumter County Gallery of Art, 200 Hasell St.

Stephen Chesley will give an artist talk at the Sumter County Gallery of Art, 200 Hasell St., at 6 p.m. Thursday, March 28. His exhibit Field, Trees, Sky will be displayed through April 19.

Special to The Sumter Item

It's not that Stephen Chesley has an ulterior motive, or even an agenda. But the work this artist creates is so obviously grounded in an ethos built on science, math, morality and preservation, there is no questioning the priorities behind his purpose and aesthetic. Chesley is devoted to what is real in the world that surrounds him - flora, fauna, grasses, gases, trees and the natural chemical alchemy that illuminates them - via firelight or the rising and setting sun. His current exhibition at the Sumter County Gallery of Art - Field, Trees, Sky - offers testament to a value system dedicated to honoring nature, preserving it for posterity, capturing it in all its wildness, and releasing it onto his canvas.

A native of Schenectady, New York, Chesley grew up along the coast of Virginia Beach before attending Clemson University and earning an advanced degree in urban planning. An art autodidact, Chesley had divorced himself from the workaday constructs of the American 40-hour week by the time he turned 30 years old, devising a personal work ethic around the creation of art and his own natural rhythms. The freedom to approach the natural world with few constraints is evidenced and celebrated in this exhibition at the small, but impressive gallery.

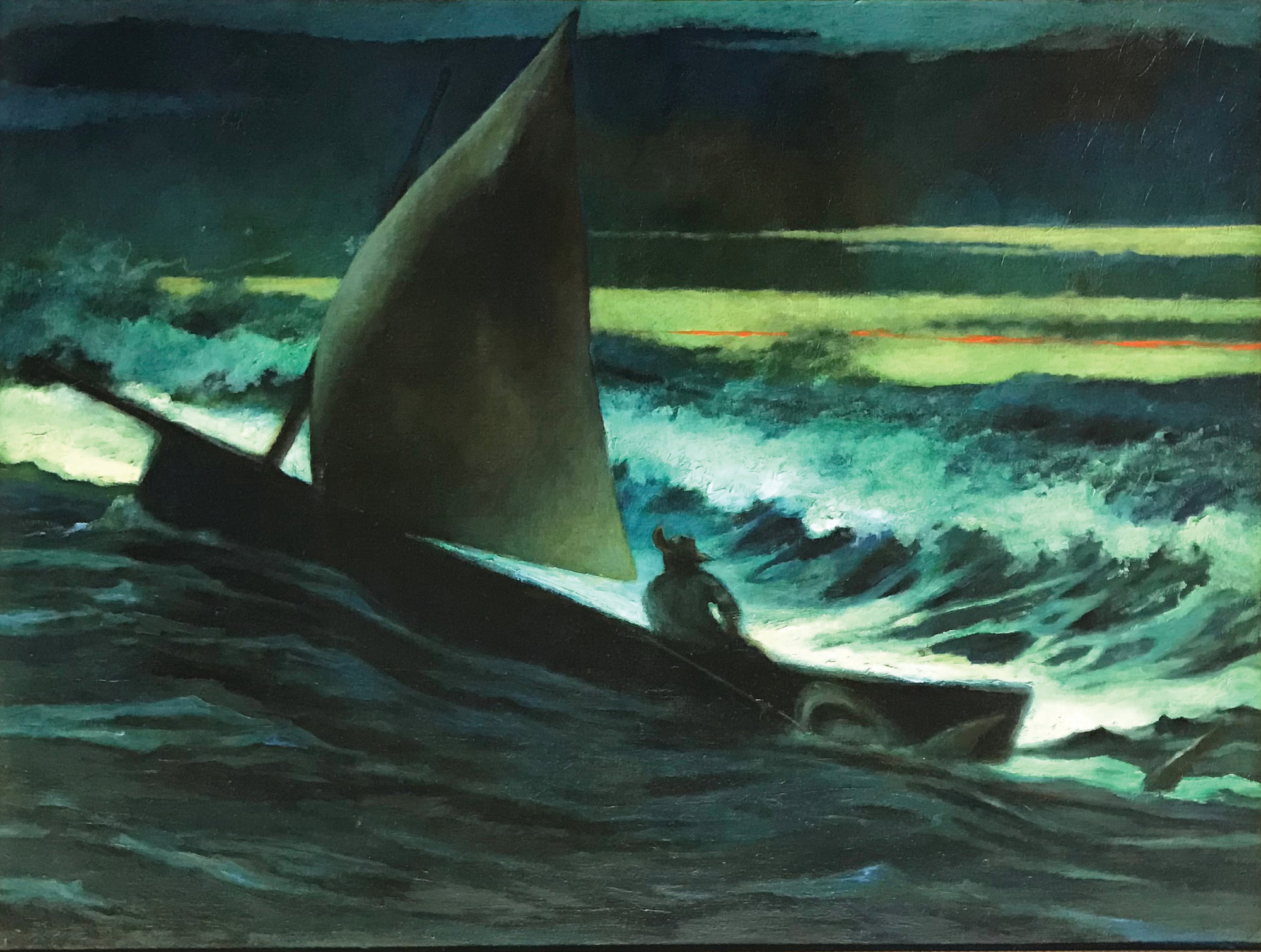

In "Twilight, Field," an oil painting from 2012, for example, the artist reveals his exacting approach to depicting the interaction of color in settings affected by specific atmospheric influences. A blushed sky with layered lemon, apricot and moss-green paints suggests the resulting scattered molecules of light that are more evident when the sun is lower in the sky, a glimpse of the marriage of science and art that Chesley so fully celebrates. We see that teasing nod to the artist's fully integrated scientific approach to art, also, in "Elliot Hitchcock and the Bull Shark's" thin orange line almost hidden in the troposphere of a long-setting sun-bringing to mind Winslow Homer's work in England, especially his "West Point, Prout's Neck" and other seascapes.

Even comparing oil to pastels, and going back to 1990 and "Trees, Marsh, Sky - Hunting Island Canvases," again we see a sky layered with colors that bleed from vanilla bean to plum and two delicate atmospheric lines suggesting a chemical reaction Chesley could likely discuss the precariousness of at length. It's in the pastel "Trees, Field" from 2003, however, where the repeating shimmering streaks of strawberry give depth to the scene as they frame a screen of cypress and late summer deciduous trees and are abutted by a cloud of powdery indigo over the brush in the forefront. The result is a deep, lush landscape that begs the viewers to enter it in their minds.

The viewer's desire to be a part of the painting is not an uncommon response to Chesley's work, particularly his firescapes, two of which are included in this exhibition. "Rain Pool, Clearing, Trees" a pastel from 1999, gives us deciduous trees devoid of leaves, bare, gray trunks and branches against a cold, blue-white sky so we assume we know the time of year, as we tend to do in almost all of Chesley's paintings. It had rained, probably that day, so it was a good day to burn off cleared brush. And the fire is so intense, so realistic - the bright orange of the sodium burn giving way to the moisture showing itself silvery white, with a halo of blue as carbon and hydrogen are released - the viewer can almost smell the troubled air. Similarly in "Dusk, Pines" an oil on board firescape from 2001, the thick brush strokes of the blaze and thicker saturation of color draw the viewer to that spot and invite us to gather there in curiosity, if not reverence.

So much of Chesley's work is invitational - beckoning the viewer to come closer, follow the natural path of the eye and explore what else the artist did not paint but implied was there for the discovering. In 1986's watercolor, "Lowcountry," what has startled the white-tailed (Virginia?) deer that the artist has captured just before she bolts? In 2018's charcoal, "Creek, Twilight," it is impossible not to wonder what is around that bend in the flowing water and beyond the largest stone. What cherished miracle of nature did he see on the other side of the prominent tree trunk in "Twilight, Creek," another oil from just last year? Whatever it is, he gave it a light that beckons us.

There is no doubting what the artist holds dear in Chesley's choices of exhibition and his treatment of the subjects. The 2015 charcoals, "Woodstork" and "Egret, Beaufort" tell us in no uncertain terms. His homescapes depicting beach houses are rich fodder for fiction as we easily imagine the multi-plot storylines that could accompany them. From his 1985 oil "Window" - in which we can only speculate on who might be napping beneath the breeze from the box fan - to the 1986 watercolor "House, Bull Island" - what figure, refreshed by the late summer wind wafting from the beach, will walk on the screened porch with a tall cold drink? - to the painting of another small white house, picnic table adjacent, awaiting someone from within to come through the screened door laden with sharp knife and watermelon, a trail of children following close behind.

And just in case the fragility of these gifts escape the viewer, Chesley posits the question, and the imperative of protection, via his 1985 still life watercolors, "Still Life with Waxwing, Watch, and Hook" and "Still Life with Thrush and Grasshopper." Bringing home the urgency of his warnings is 2017's profoundly beautiful, lush, rich painting, "The Last Fish on Earth," possibly the most stunning painting the artist has ever given us.

Stephen Chesley's Field, Trees, Sky will be on exhibit through April 19.

More Articles to Read