Uncovered: A speeding truck near Sumter. An elderly woman left in a ditch. The mystery of Ada Wright.

South Carolina has seen an increase in fatal hit-and-runs across the state in the last five years.

The South Carolina Department of Transportation reported 18 wrecks where 20 people died with an unknown driver in 2017. In 2021, 30 wrecks resulting in the same numbers of deaths were reported.

In Sumter County, only one fatal wreck with one death was reported from a hit-and-run in 2017 while two died during hit-and-run wrecks in 2021.

While thousands were injured in hit-and-runs across the state, Sumter reported an increase in vehicle injuries as well.

In 2017, 37 were injured in 21 hit-and-runs. In 2021, that increased to 54 injured in a total of 36 wrecks.

So far this year, as of mid-March, the state reported four wrecks where four died by a hit-and-run. Sumter has reported no fatal hit-and-run wrecks, but 11 have been injured.

This article was produced in collaboration with The Sumter Item as part of the Uncovered project, an initiative in which The Post and Courier is partnering with 18 community newspapers to expose questionable conduct by government officials across South Carolina. To read more Uncovered investigations, CLICK HERE.

tbartelme@postandcourier.com

SUMTER — One muggy afternoon in August 2017, a 76-year-old woman named Ada Wright walked across the busy road outside her home to collect her mail.

Wright knew the road was dangerous; U.S. Highway 15 here had seen its share of wrecks. So she was careful as she crossed. Suddenly, she saw a white vehicle speeding toward her.

She remembers watching it veer onto the road’s narrow shoulder. She remembers locking eyes for an instant with the driver. She remembers diving at the last second into a deep drainage ditch to avoid being struck, then lying there as the vehicle drove off.

And she remembers the shards of pain in her ankle, how she couldn’t move her legs, how she could only lift her hand and wave it, hoping someone would notice.

All of that remains clear in her mind. But what happened after that day remains murky. Her case generated an early lead that led to a deputy at the Sumter County Sheriff’s Office. It led to an investigation by the same department, an investigation that went nowhere. It led to conversations with State Law Enforcement Division agents, which also went nowhere.

Wright’s unresolved case also has parallels with another mystery in Sumter County, this one involving former sheriff’s Lt. Melissa Addison.

***

Related story: Uncovered: A Sumter, South Carolina, sheriff. A rape claim. And silence from SLED.

***

Addison alleges that Sheriff Anthony Dennis sexually assaulted her. But SLED agents failed to interview witnesses or log the case in the agency’s management system, lapses that SLED Chief Mark Keel later acknowledged in a January Uncovered report. SLED has since launched a new investigation into Addison’s allegations. Dennis has denied any wrongdoing.

The same SLED agent who mishandled Addison’s case also looked into Ada Wright’s. And as happened in Addison’s case, the agent didn’t document what he did, effectively removing it from the agency’s normal review processes.

Together, the two cases raises questions about how SLED opens and manages cases, especially ones involving tips against fellow law enforcement officials.

And Wright’s case also highlights the sheer number of wrecks in South Carolina in which the drivers were unknown: About 3,600 incidents in 2021 alone, according to the Department of Public Safety. Those wrecks injured nearly 4,800 people and killed 30.

Amid these questions and unsolved cases, Wright’s case grows colder by the day.

Here’s a deeper look at how it unfolded.

***

Before the afternoon of Aug. 14, 2017, Ada Wright took care of a mentally disabled patient, spent time in her garden and drove herself to church. But when she dove into that 3-foot drainage ditch, she shattered her ankle.

Minutes passed. Car after car passed. Then a woman named Crystal Ridgeway noticed a hand waving from the ditch. She stopped and called 911. A neighbor came out to see what was happening. She saw Wright lying there in pain and feared that fire ants might get to her.

“She told me that someone came flying down the road right at her, and she saw his face,” the neighbor said, asking that her name not be published because she feared for her safety. Paramedics eventually took Wright to the hospital.

Wright’s daughter, Gale Wright-Lyons, was furious about what happened, and grew angrier when she thought the Sumter County Sheriff’s Office wasn’t taking the case seriously.

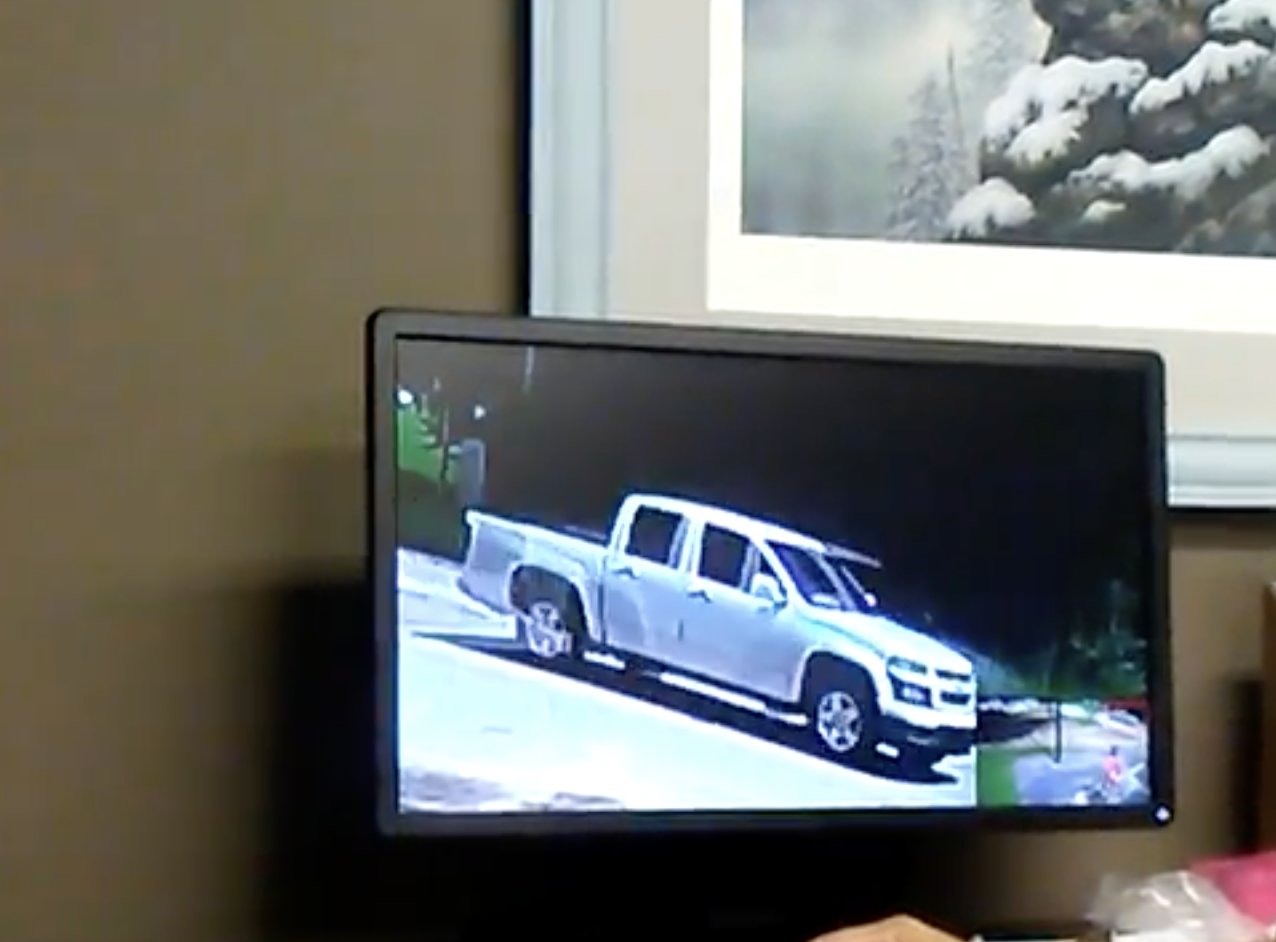

Wright-Lyons is an insurance claims adjuster who studied criminal justice in college. She began her own investigation, looking for nearby homes and businesses with surveillance cameras pointed toward the road. A construction company within sight of the mailbox had several cameras. She contacted the business owner and a sheriff’s investigator. They gathered around a computer monitor and watched the footage.

The video showed Ada Wright walk to the mailbox and suddenly disappear. At about the same time, two white vehicles sped past, a Chevy pickup in the lead followed closely by a white Toyota pickup with a camper shell. (Wright-Lyons shared a clip with The Post and Courier showing the vehicles.)

Wright-Lyons began asking residents and businesses in the area about the vehicles. She learned that a Sumter County deputy who lived in the area also had a white pickup. Property tax records showed the deputy’s pickup truck was a similar make and color as the one in the surveillance video, a finding The Post and Courier confirmed.

Several months later, Sumter County Sheriff Chief Deputy Hampton Gardner phoned Wright-Lyons with an update, and she recorded their conversation.

Gardner said investigators had turned over a file to prosecutors.

“We’re trying to see if we have enough to make a charge on the vehicle we’ve got,” Gardner said in a recording Wright-Lyons provided.

Wright-Lyons later met with 3rd Circuit Solicitor Ernest “Chip” Finney III, who told her he hadn’t received any information that “would help us narrow down whatever happened,” according to a recording of their conversation. Finney did not return calls seeking comment.

In a recent interview, Gardner said his department’s investigators distributed photos of the white pickup and issued bulletins asking the public for help.

“One of the family members were alleging that a deputy within the agency had a vehicle that fit the description,” Gardner said. “But we were not able to determine that at all.”

Gardner said the department would have asked SLED to do an independent investigation had the situation warranted. But the department declined to go that route. As it stands now, the department has classified the case as unfounded, he said.

“We just couldn’t find anybody to determine what happened.”

***

As months passed without any resolution, Wright-Lyons pressed SLED to investigate. She spoke with SLED Capt. Johnnie Abraham, who at the time was in charge of the agency’s Pee Dee region. Abraham had been in law enforcement for four decades and had received many honors. Wright-Lyons also recorded their conversations.

In one, Abraham can be heard saying that he received “a whole case file” from the Sumter County Sheriff’s Office. He mentioned that he’d seen photos and videos. “I was going through all that.”

Abraham told her that he’d contact the sheriff (Anthony Dennis), and try to determine “if they neglected to do something, or if there’s anything we can do that they haven’t done. But I’m not investigating the Sheriff’s Office, now.” He said he’d get back to her.

She never heard from him.

Frustrated, she phoned another SLED agent assigned to the Pee Dee area. He didn’t seem familiar with the case but said he would get back to her. She and her mother never got a call, they said.

In December, Abraham died of COVID-19, just before he was set to leave his SLED post for a job as chief deputy of the Florence County Sheriff’s Office.

Despite Abraham’s claim to Wright-Lyons about having a case file, SLED has no documents in its file system, the agency told The Post and Courier after the newspaper submitted a Freedom of Information Act request.

The Sumter County Sheriff’s Office never requested SLED’s help, so the agency never formally opened a case, said Ryan Alphin, SLED’s executive affairs director.

But a similar absence of basic record-keeping happened in the case involving Addison, the former lieutenant, and her allegations that Sheriff Dennis sexually assaulted her in 1997 and 2004.

Addison provided Abraham with lists of witnesses to corroborate her story. But no witnesses were contacted.

Agents also failed to enter documents and evidence in the agency’s management system.

Forgoing this basic procedure effectively removed Addison’s allegations from a regular agency review process.

When confronted with the lapses in Addison’s case, SLED Chief Keel acknowledged it wasn’t handled correctly.

“Unfortunately, and to be perfectly honest, it sort of fell through the cracks,” Keel said at the time.

But Alphin said Wright’s case was different.

“Reviewing another law enforcement agency’s handling of a case as a professional courtesy is not comparable to SLED criminally investigating a law enforcement officer’s conduct,” he said.

***

As time passed, Ada Wright grew weaker and weaker. After her surgery, arthritis set in.

Now 80, she was confined to her bedroom one recent afternoon as Wright-Lyons tended to her.

Wright said she needs a wheelchair to move around. She can’t work in the garden anymore.

“I can’t do what I used to,” she said. At the very least, she added, “I’d like the person who almost hit me to apologize.”

But her daughter said an apology wasn’t enough.

She said that victims deserve justice — and delaying an investigation or sidelining it only adds to a victim’s pain.

***

LISTEN: To listen to emergency 911 calls made after Ada Wright of Sumter fell into a ditch after she said a white vehicle nearly struck her, CLICK HERE. (Provided/Sumter Police)

***

Shelbie Goulding and Kayla Green of The Sumter Item contributed to this report.

More Articles to Read