Uncovered: South Carolina Department of Natural Resources rakes in millions from pharma company it regulates

1. Of monkeys

MORGAN ISLAND - As your boat speeds toward South Carolina's island of monkeys, you see a forest of tall pines and oaks rising from the salt marsh. Then a sliver of beach. And signs warning that you're under surveillance.

Slowing now in the shallows, you see no movement, except high in the pines as branches catch the breeze - no movement until your eyes adjust to the shadows below, and there they are. Monkeys with pink faces and brownish gray fur. Lots of them.

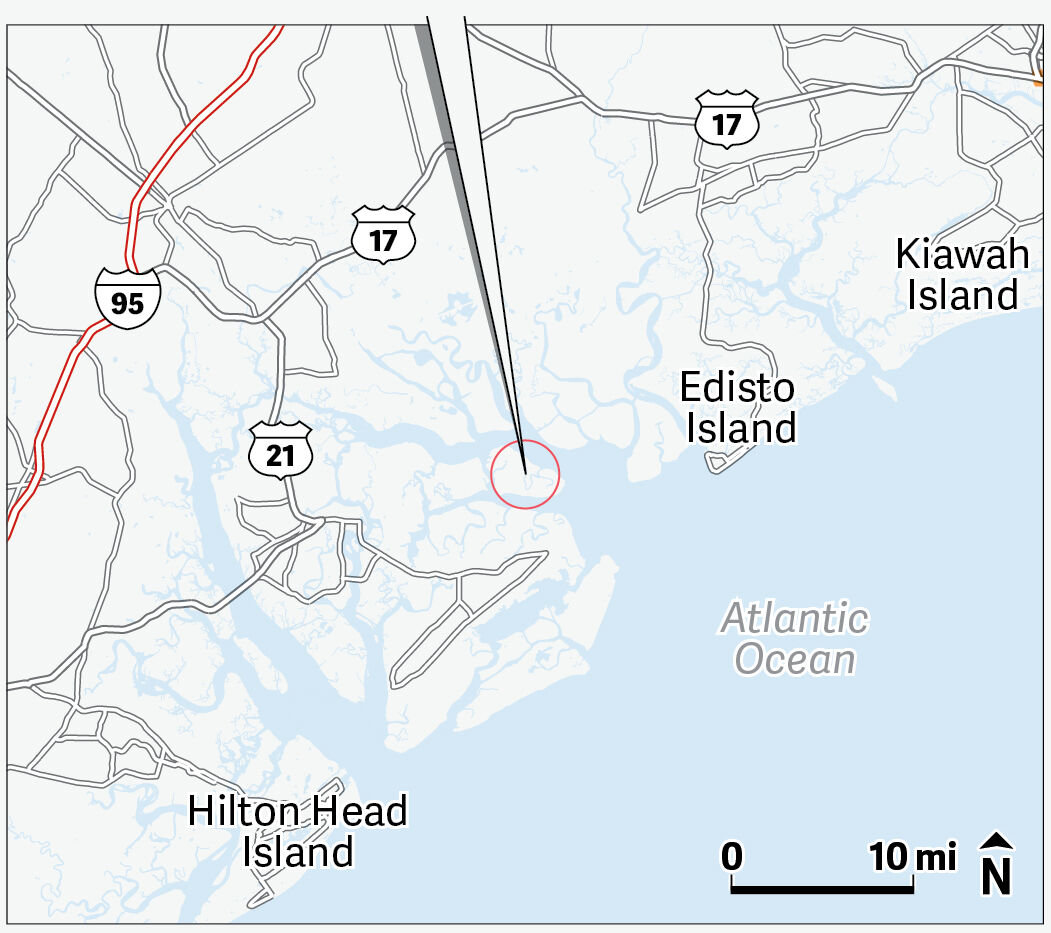

About 3,500 rhesus monkeys live on this remote island - more than the human population of Folly Beach. Unlike Folly Beach, Morgan Island has no roads or restaurants. Just lots of monkeys. They leap from limb to limb. Two groom each other on a fallen tree. A scuffle suddenly breaks out, triggering screeches and blurs of arms, legs and tails.

It's an odd sight, monkeys roaming on an island in the heart of the ACE Basin, coastal South Carolina's conservation jewel. And it marks an equally out-of-place arrangement between industry and government.

In this relationship, a pharmaceutical and animal breeding company, Charles River Laboratories, pays the state Department of Natural Resources nearly $1.5 million a year to lease the island.

DNR then uses this $1.5 million windfall to help pay salaries of employees, including some who regulate Charles River's other money-making ventures, a Post and Courier Uncovered investigation found. And just last fall, Charles River dangled an additional $500,000 for a special "biomedical research license," an offer DNR eventually refused.

Critics say the cozy relationship between DNR and Charles River distorts the agency's priorities and taints its independence. They argue that DNR can't properly regulate a $3.5 billion company that covers some of its paychecks. And that offer of $500,000?

"I've never seen anything like it," said Christian Hunt of the environmental group Defenders of Wildlife. "It's a gross conflict of interest, to put it simply."

Charles River executives said their $500,000 offer didn't come with strings. They merely wanted to help an agency that has seen its budget slashed.

"It wasn't a pay-to-play, you know," said Greg Marshall, a corporate vice president. "We know they have limited resources. We've been working with them for 25 years. They didn't accept. That's fine."

And Robert Boyles Jr., DNR's director, said his agency depends on the Charles River money, for better or worse. If the agency wasn't a landlord to a monkey farm, he said, "there'd be quite a few people looking for other work."

He added that DNR's relationship with Charles River evolved over time, sometimes with surprising twists. But in the wake of the Uncovered project's findings, he said he has concerns.

"I'll just be blunt. It never crossed my mind that there's a conflict of interest or an appearance of a conflict."

The agency's predicament offers a larger lesson: How conflicts of interest can form incrementally until an agency finds itself mired in an ethical swamp.

In this case, it's a lesson that goes beyond monkeys, one that involves tens of millions of dollars, scientific discoveries, politics and lobbyists.

And blood.

Blue blood.

2. Of blood

Horseshoe crabs have existed for at least 445 million years, before the dinosaurs, and their blood is milky blue. The tint comes from copper, which turns bluish when exposed to oxygen, just as iron in human blood turns red when exposed to air.

The crab's blue blood is incredibly valuable. It contains amebocytes, part of the crab's ancient immune system. A chemical in these amebocytes has a special ability to detect toxins. Decades ago, scientists figured out how to create an extract that detected deadly bacteria and fungi. They named the extract LAL, short for Limulus amebocyte lysate. They used it to make sure vaccines and other drugs were free from contamination.

It was a huge advance that made medicines safer, including coronavirus vaccines. Astronauts on the International Space Station even used LAL to detect toxins. Demand for LAL rose like the rockets that propelled it into space. A gallon might fetch $60,000. Today, Charles River is one of the world's main producers of this lifesaving extract.

The company's roots stretch back to 1947 when its founder, Henry Foster, bought a thousand rat cages from a farm in Virginia. Traps in hand, Foster set up a rodent-breeding lab along Boston's Charles River and delivered rats to researchers.

Over time, Charles River expanded across the world, building its business largely on animal breeding operations, then moving into drug development. By 2021, the company had about $3.5 billion in revenue, $400 million in profits and 18,000 employees. Part of its ongoing success involved bleeding horseshoe crabs.

Horseshoe crabs are tough creatures that can live for months without eating. Genetically, they're closer to scorpions and spiders. Unlike scorpions, horseshoe crabs are harmless, though with their spikes and helmet-shaped shells they look scary.

"People get freaked out because they have squirmy legs. And they look like small tanks because they've got a big shell and a spiny tail," said David Mizrahi, co-leader of the Horseshoe Crab Recovery Coalition, a group pushing for more restrictions on crab harvesting. "It's just a creature that most people are not used to seeing in the wild. But they're not dangerous at all."

Beginning in the 1850s, harvesters collected horseshoe crabs for fertilizer and livestock feed. Later, they used them as bait in whelk and eel fisheries. Then, in the late 1960s, a pharmacologist named James Cooper helped pioneer a new use: Using their blood to detect toxins.

Cooper eventually formed a small biotech company in Charleston called Endosafe. He and his colleagues began pushing South Carolina lawmakers to ban commercial harvesting - except for biomedical uses. In 1991, legislators passed a law that did just that. Cooper's company suddenly had a protected supply of horseshoe crab blood.

Charles River bought Endosafe in 1994.

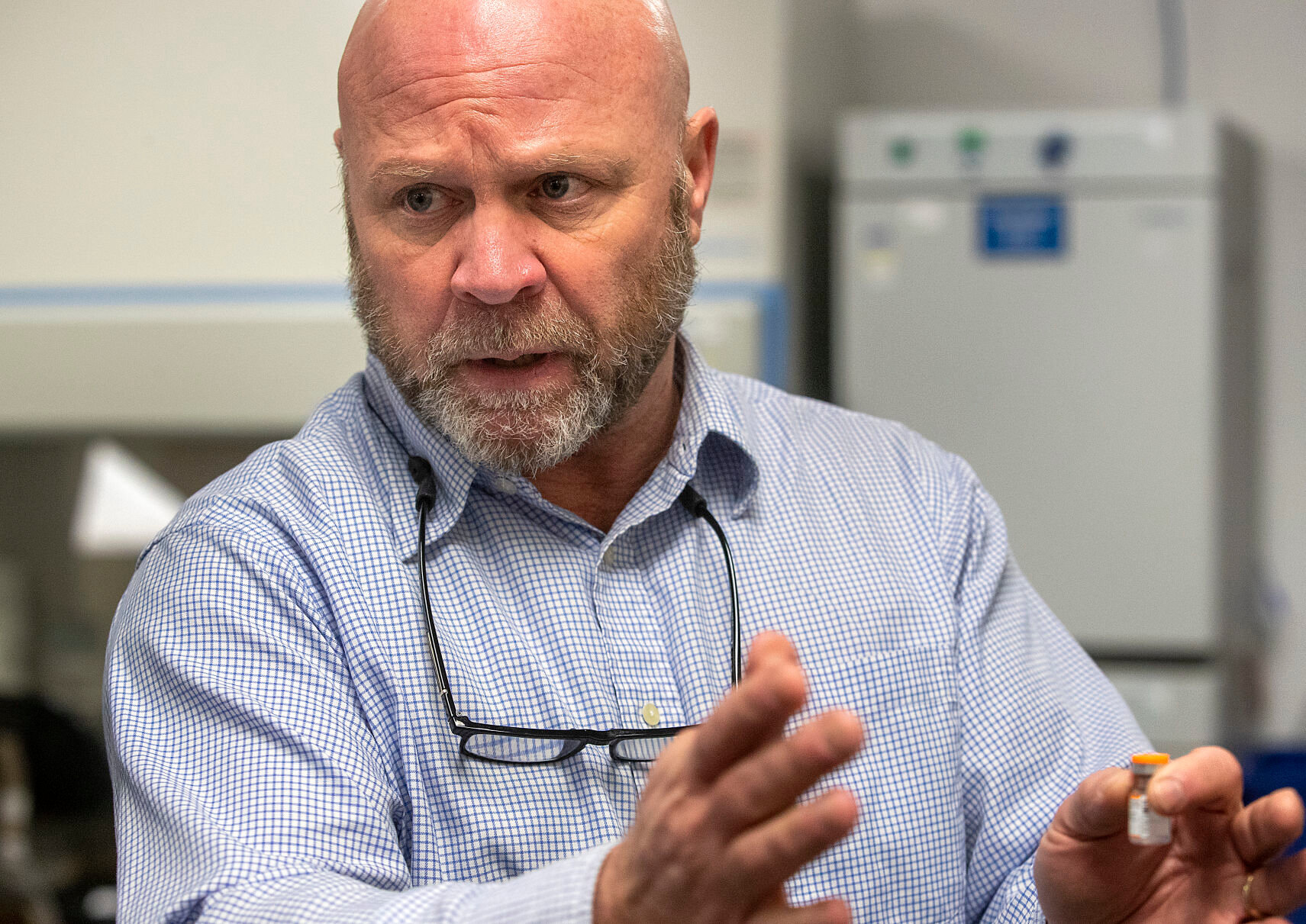

Today, the company hires licensed fishers to collect crabs on the South Carolina coast in spring when they come ashore to breed. The exact number they cull is kept under wraps - state law prohibits DNR from releasing trade secrets to the public. Charles River contractors then haul the crabs to holding ponds or directly to the company's extraction lab in Charleston.

The lab is in an industrial building off Wappoo Road, west of downtown Charleston. There, staffers line crabs on long metal counters and strap them into place. Then they insert tubes into the crabs' hearts and extract their blood. A large crab can produce as much as a cup and a half.

Cooper, the founder of Endosafe, last year likened the process to human blood transfusion. But unlike human blood drives, anywhere from 6 percent to 30 percent of these crabs die after being bled, studies have shown. Survivors are often left weaker.

Along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, five companies, including Charles River, harvest more than 550,000 crabs a year, up 63 percent from 2004. Populations have crashed in some places, especially the Northeast where commercial fishers and LAL harvesters compete. The crab's decline rippled through the food web.

A female horseshoe crab can lay tens of thousands of eggs. Those eggs are a critical source of food for shorebirds such as the red knot, now an endangered species. South Carolina's crab numbers appear to be stable but show troubling downward signs.

Charles River Labs officials insist its harvesting has had little or no impact, though they acknowledged that data on South Carolina's crab population is lacking.

"We believe that we're only collecting a small percentage of the amount of horseshoe crabs that are out there, but we don't have the data," said Marshall of Charles River. "We're the first ones to admit it."

Still, conservation groups fear for the ancient creature's future given the demand for its blood. They want the government and medical industry to use a synthetic alternative.

"There's really no reason to harvest crabs," Mizrahi said.

Against this backdrop, Charles River has taken pains to protect its business interests.

Which takes us back to Monkey Island.

3. Of money

The monkeys arrived in South Carolina in 1979, packed in crates and stowed in the belly of chartered DC-3s.

They'd come from a colony in Puerto Rico established in part to test polio vaccines. The federal government wanted new breeding colonies in the United States. And Morgan Island was one of the new sites.

The first plane touched down on a moonless night at Beaufort's Marine Corps Air Station.

Former Beaufort Mayor David Taub helped start the colony and described its history in a column for The Island News:

"Marines came out to witness this spectacle as we unloaded monkey crates onto a trailer," he wrote. " Early the next morning, we loaded crates onto our boats for the seven-mile trip to Morgan Island."

Soon, he and other locals began calling it Monkey Island instead.

Morgan Island has about 400 acres of high ground but is surrounded by more than 4,500 acres of creeks and marsh. It takes between 30 minutes and an hour to reach the island from public boat landings in Beaufort or Edisto Island.

Despite its remote location, at least seven monkeys escaped between 1980 and 1996, DNR reported in 2002. All were recaptured, including one on Lady's Island more than 6 miles away.

- - -

In 2002, developers targeted the island, laying out plans for 64 homes. Officials at DNR wrestled with a decision to buy it. At the time, Boyles was DNR's policy director. He put together a report on the pros and cons.

On one hand, buying Morgan Island would be a big win for the ACE Basin's long-term future. This marshy confluence of the Ashepoo, Combahee and Edisto rivers was one of the least-developed estuaries on the East Coast. The agency was proud of this public and private campaign to preserve the area. Buying Morgan Island would cement that progress.

On the other hand, his report continued, what would they do about the monkeys? If taxpayers own the island, shouldn't they have access to it? Were the monkeys a health risk? A legal liability? They were known carriers of a herpes virus that, though rare, could be lethal to humans. If DNR bought the island, it would have to be off limits to the public.

Then again, there was the money.

At the time, an animal breeding company called LABS of Virginia managed the monkey colony. LABS leased the high ground from the island's owner, a corporation called Morgan Islanders Ltd., for $325,000 a year. If DNR bought the island, it would inherit that lease money.

After weighing the pros and cons, DNR decided to buy Morgan Island for $20.5 million with federal money.

Boyles recalled that board members thought they'd just let the lease expire.

"The thinking was that we'll have the feds take their monkeys, and we'll have a piece of protected land. But then there was an election."

In 2003, incoming Gov. Mark Sanford installed new board members, people with more business-minded goals.

"When Sanford's board came in, there was a thought that this lease can generate revenue," Boyles recalled.

This came as state lawmakers hammered away at DNR's budget. From 2000 to 2004, the state's allocation for DNR's marine division went from about $5 million to just over $1 million. Dozens of positions were eliminated.

"Then, one day in 2007, out of the blue, we got a phone call from Charles River saying, 'We're the new monkey managers,'" Boyles said.

He was surprised. The federal government hadn't consulted with DNR. It was akin to a landlord learning a new tenant had moved in without notice.

In the wake of this confusion, DNR eventually renegotiated the lease and hiked the rent to about $900,000 a year, with 5 percent annual increases.

Now DNR was making real money.

***

By 2021, Charles River was wiring about $1.5 million into DNR's coffers each year, records obtained by The Post and Courier show.

And that Morgan Island money went directly to DNR's hard-hit Marine Resources Division - the department that also monitors horseshoe crabs.

Last year, Charles River's lease payments paid part or all of the salaries of at least 33 employees, DNR records show.

This includes a partial salary for Phil Maier, a DNR deputy director who died in December, and Blaik Keppler, who took over for Maier.

Charles River money covered partial salaries for Michael Denson, director of a division that does research, including work on horseshoe crabs.

It partially paid for two DNR turtle researchers, eight ACE Basin staffers and six employees who respond to sudden deaths of fish.

It provided a $275,000 injection into the agency's operating budget to cover office supplies and other needs.

Has the monkey money also bled into DNR's efforts to monitor horseshoe crabs?

4. Of conflicts

A look at internal DNR text messages and emails reveals numerous exchanges between DNR officials and Charles River executives and suppliers. They show DNR biologists asking for everything from advice on horseshoe crab traits to feedback on grant proposals.

Other documents show the agency soft-pedaled potentially negative information about horseshoe crab harvesting.

For instance, every spring, DNR staffers collect horseshoe crabs and measure them. In 2009, the agency reported that the crab population "appears strong."

Then, in 2010, staffers collected fewer crabs during regular inshore surveys, and the crabs they caught were smaller and weighed less.

At the same time, offshore trawls suggested numbers were increasing.

Despite this conflicting data, the agency said the lower inshore counts didn't reflect the "lower abundance" of horseshoe crabs. Year after year, the agency repeated the same language in its reports.

Then, in 2016, a change: Charles River stopped collecting crabs as it built its $11 million lab expansion in Charleston. Crab numbers that year suddenly rebounded, a finding first reported by The State. When Charles River began collecting crabs again the next year, DNR saw its inshore and offshore crab numbers go back down.

In public, Charles River and DNR dismissed the notion that crabs here were in trouble. Inside the agency, there were concerns.

At about this time, a DNR researcher drafted a grant request to North Carolina Aquariums for a new study: "This project is timely because the SC HSC (horseshoe crab) population could be declining below a sustainable level, but the status of the population is currently unknown."

Meantime, another scientist emailed Mike Denson, the research institute director, with an idea: Renovate greenhouses at the Waddell Mariculture Center near Bluffton to study effects of extracting blood from horseshoe crabs. Previous studies in other states showed the extraction process left crabs weaker and disoriented, possibly contributing to population declines.

Two hours later, Denson shot down the idea. "I'm not sure investing more funds into horseshoe crabs is a worthwhile endeavor," he wrote. "It's one of the least important resources we are working on We do not work for (Charles River's) Endosafe " Part of Denson's salary was covered by money from Charles River's Morgan Island lease money.

Meantime, the S.C. Sea Grant Consortium and DNR began a new study, one that looked at the health of the crabs' gene pool. If researchers found signs of inbreeding, that might mean the overall crab population was in decline. Charles River chipped in about $53,144 toward its expenses. The study found the gene pool was healthy.

"We had green check marks all the way down the list," Tanya Darden, the study's lead author, was quoted as saying in a 2016 press release by the Sea Grant Consortium. "We found no conservation concerns based on genetic diversity."

A scientific journal later published the findings. The paper didn't cite the Charles River funding.

Charles River later crowed about the study on its website: "So what can we infer from these findings by SCDNR? One conclusion might be that conservation practices are working here." Again, there was no mention that it had paid for part of the study.

In a recent interview, Darden characterized the study in less definitive terms. The sampling was a one-time effort - a snapshot of "what it was at this time and place." The agency needs more studies to pin down whether the population has increased or decreased, she said.

Another telling example: In 2017, a College of Charleston graduate student had finished a two-year project that found that crabs in holding ponds showed signs of stress and declining health.

It was another potential dent in Charles River's arguments that bleeding was harmless.

The grad student eventually went to work for DNR. Upon her arrival, Peter Kingsley-Smith, DNR's shellfish section manager, said DNR officials were concerned about some of the more negative findings.

The horseshoe crab fishery is "a sensitive one," Kingsley-Smith noted in an email, and then demanded to see all future drafts of manuscripts based on her findings.

She eventually submitted a paper to a scientific journal, and DNR officials commented extensively on her drafts. In one, a biologist wrote that horseshoe crabs were vulnerable to extinction. Delete that language, the biologist wrote, saying it was "alarmist," and that "all animals are vulnerable to extinction."

Boyles said he doesn't believe that the Charles River money has compromised the agency's independence. He said he wasn't concerned that Charles River's $53,144 contribution to the gene study would skew the results. And it's common for staffers to comment on drafts of scientific papers.

"We are interested in long-term health of the (horseshoe crab) resource, and I think Charles River is as well," Boyles said.

5. Of secrecy

All this comes amid increasing legal, economic and political threats to Charles River's lucrative crab and monkey operations.

In December, South Carolina Congresswoman Nancy Mace chartered a boat to take reporters and animal rights activists to Morgan Island. It was a floating press conference to highlight her concerns about using monkeys to test medicines. As the boat approached the island, workers there appeared to shoo away any lingering monkeys.

Three conservation groups recently sued DNR and Charles River in federal court. The groups - Defenders of Wildlife, Coastal Conservation League and Southern Environmental Law Center - alleged that DNR failed to properly regulate horseshoe crabs. They argued this failure also threatened the red knot, the endangered bird that feeds on horseshoe crab eggs.

Previously, the groups sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, alleging Charles River illegally collected crabs in Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge. State Attorney General Alan Wilson sided with Charles River in that court fight. A federal judge eventually ordered the practice stopped.

As pressure grows, Charles River has taken pains to guard and shape its public image.

Earlier this year, two Post and Courier reporters asked Charles River for tours of its Charleston bleeding operation. The company's marketing consultant said yes to one reporter and no to another - no to the reporter who had filed numerous records requests with DNR about the company. How did Charles River learn about these requests? By filing their own to find out who was asking questions about the company, DNR confirmed.

In interviews with The Post and Courier, Charles River officials declined to answer questions about how many monkeys had escaped since it took over the Morgan Island colony, whether it plans to continue its operation there in the long term and how much money it makes breeding the animals.

But the company has been more open about activities that cast it as a responsible steward of nature. It donated $75,000 to the S.C. Aquarium since 2019. It was a top sponsor of the Conservation Voters of South Carolina Green Tie Award.

Meantime, Charles River enlisted the help of McGuireWoods Consulting, a firm that includes heavy-hitter lobbyists such as former Gov. Jim Hodges and ex-state Rep. Billy Boan.

In October, Brian Flynn, another lobbyist with the firm, made an unusual proposal: Charles River would pay DNR $500,000 for a special "biomedical research license," according to an email obtained by The Post and Courier, which DNR heavily redacted.

It was a stunning move. A commercial fishing license typically costs $25, and a license to collect crabs for LAL is free. Why offer its regulator half a million dollars?

The company wanted to help DNR study whether horseshoe crab numbers were going up or down, said Foster Jordan, corporate senior vice president.

"If we could donate some money," he said, "or help you (DNR) with regulations, help you with research to help keep us here and convince everybody that what we do is ethical, correct and right for the species - we're willing to do that. They refused it. They didn't want it."

None of this information was made public until reporters began asking questions.

Such secrecy has long frustrated conservation groups.

"For a public resource, horseshoe crabs are managed in the most clandestine way possible," said Christian Hunt of Defenders of Wildlife. "Charles River has a vested interest in concealing where it's harvesting and how many crabs it's harvesting. I think that if the public were to see that information, they simply wouldn't stand for it."

And in this vacuum of information, some fear the agency has lost its way.

Sally Murphy, a former DNR scientist known for her turtle research, said she worries what might happen if monkeys escape and establish a wild colony, as has happened with wild boars.

"The ecological integrity of the ACE Basin is more important than money. End of story."

6. Of more monkeys

In 2017, DNR signed a new five-year lease with Charles River. The lease gives Charles River options to renew for another five years in 2023 and in 2028. And the new lease had better terms - for Charles River: Instead of 5 percent increases every year, Charles River now would see no rental hikes for the first three years and then 2 percent a year.

Boyles said canceling the lease wouldn't be easy and likely would trigger complex negotiations with an alphabet soup of agencies. And DNR would have to find a way to make up for that loss of money or face Draconian staff cuts. He said he hasn't thought about what the agency will do when the Morgan Island lease finally expires in 10 years.

More clear: The agency needs to find ways to insulate itself from any conflicts of interest, he said.

"If people don't trust us, that's a concern, especially if there's sense that there's something nefarious happening or something doesn't look or smell right."

He said of the Uncovered investigation's findings: "You've given us a lot to think about."

***

Back in the waters off Morgan Island, the monkeys roamed along a sunny spot on the beach next to no trespassing signs that warned: "DO NOT FEED, APPROACH, DISTURB, MOLEST OR INJURE THE ANIMALS."

The sun's warmth apparently made this side of the island a popular place that day. From a boat you could see a baby clinging to an adult. A young monkey raced up a tree and jumped to another branch.

The other side was less popular, where caretakers unload barges packed with bags of monkey chow. On this morning, no monkeys could be seen here, and the docks were empty, save for a white pickup truck.

It parked at the edge of the dock, with two people inside wearing masks. They stared at a photographer from the newspaper. When he lifted his camera, the pickup driver quickly shifted into reverse, backing fast into the shadows, out of view.

More Articles to Read