Uncovered: Mayesville elected a new mayor. Then things got weird.

This article is part of The Post and Courier's Uncovered project, an ongoing initiative to shed light on corruption in South Carolina. The Post and Courier has partnered with 18 community newspapers, including The Sumter Item, across the state to bring investigative journalism to light. To read more Uncovered articles, visit www.postandcourier.com/uncovered.

MAYESVILLE — Chris Brown's 27-vote margin of victory in the November mayor's race was nearly a landslide in this small town, where more than half of the population showed up to cast a ballot.

Winning would turn out to be the easy part.

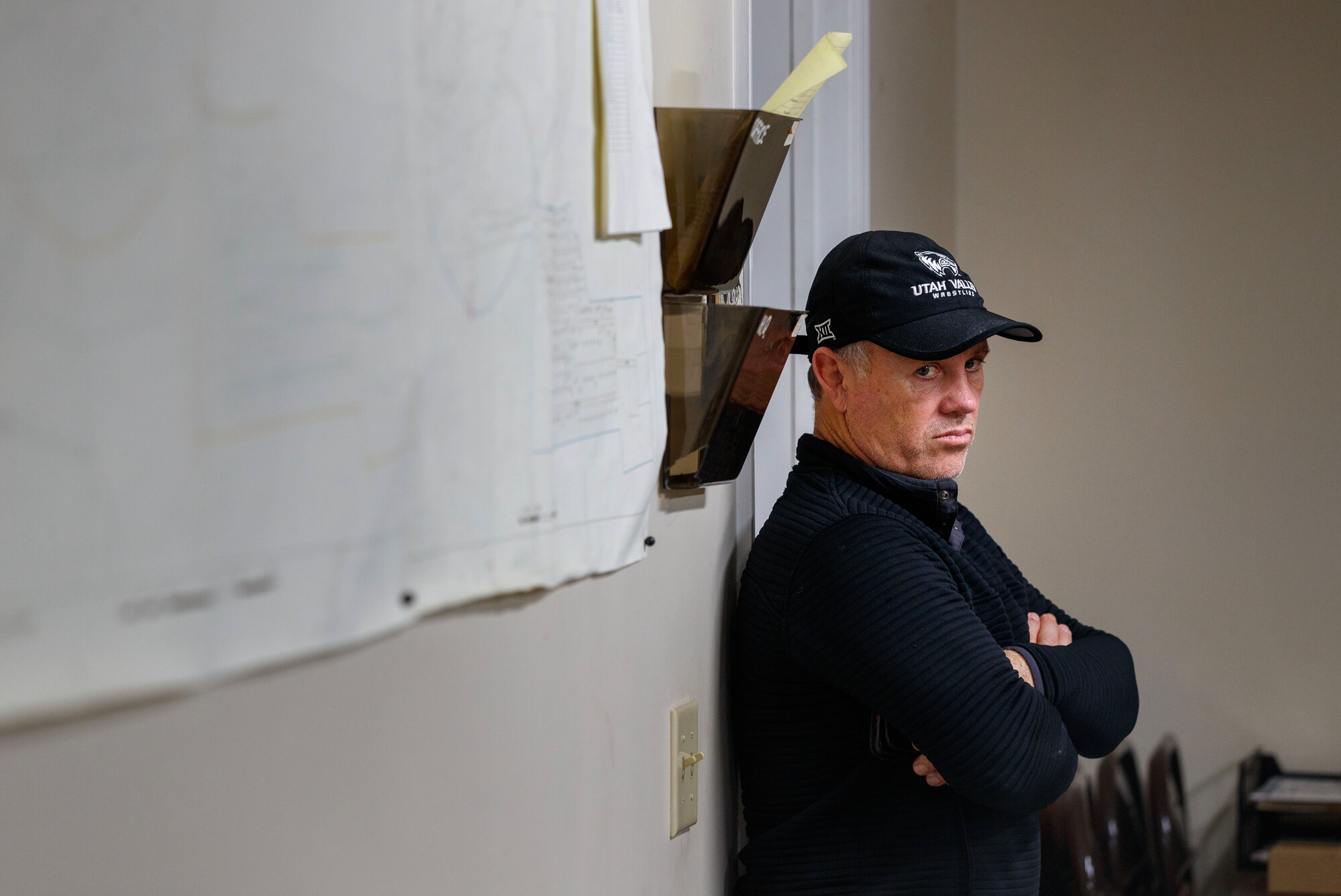

Brown moved to South Carolina from Utah two years ago. Last fall, he stunned many locals by unseating Mayor Jereleen Miller, whose family roots in Mayesville reach back centuries. But despite his new title, Brown soon found he couldn't even get the keys to town hall after being sworn in.

His election victory set off a power struggle steeped in long-simmering tensions about race, family feuds and competing visions for what should become of this struggling former railroad town on the outskirts of Sumter County. The episode has also exposed the limits of state oversight and intervention when it comes to policing municipal finances.

As a result, town business has ground to a halt.

"141 to 114," Brown said, noting the vote total in the Nov. 7 mayoral election. "And then it was just all downhill from after that. I have zero power right now."

The new town hall, renovated in recent years with more than $1 million in county and federal grants, serves primarily as a museum to tell the story of Mayesville and its most-famous native daughter: pioneering Black educator and college founder Mary McLeod Bethune. She grew up here and was a sister of Miller's great-grandmother.

The Millers — Jereleen and her husband, Ed — have the keys to the building. Thanks to a quirk in how the renovations were financed to include four public housing units, Ed Miller controls the deed as well.

They've used that power, Brown said, to lock him out of parts of town hall and move his office into a small room where the town clerk also works. Brown said Ed Miller refused to give him a key to the building, even after Brown got the sheriff's office involved. In response, Brown is working to cut off the building's municipal funding. Mayesville taxpayers pay the electricity, water, sewer and internet bills.

The dispute has spurred official complaints to state and local officials from both sides, each accusing the other of a wide range of misconduct. Brown points to a hastily approved — and apparently incomplete — audit that Miller oversaw in her last act as mayor, as well as his difficulty getting access to town financial records. The Millers, in turn, accuse Brown of stealing a box of town records that the new mayor said are secured in one of the few buildings the town still owns. And some question the ethical implications of having the now-former mayor's husband lead the nonprofit formed to help change the blighted town's fortunes.

The Post and Courier partnered with The Sumter Item to examine these issues as part of its Uncovered initiative, an ongoing collaboration with community newspapers to investigate instances of questionable government conduct across South Carolina.

Brown's chief ally among town leaders is Reggie Wilson, a suspended town councilman. Gov. Henry McMaster benched Wilson after he was indicted in 2022 on charges of threatening Jereleen Miller's life outside town hall by making gun noises with his mouth. Wilson acknowledged yelling obscenities that day but said he never threatened anyone's life.

The clerk, Taurice Collins, has accused the new mayor of discriminating against her because she is Black. She filed a complaint to that effect with the state Human Affairs Commission in December. She has warned the Town Council that Brown, who is white, is pursuing a hidden agenda and attempting to fire her.

Brown said Collins seems to be working for the Millers instead of the town. But she reports to the council, not the mayor.

And during Brown's first meeting as mayor, two council members walked out.

'Nothing to hide'

Mayesville is a cotton town in Sumter County founded around a rail stop in the 1850s. The banks, restaurants and shops that called Mayesville home are long gone. They're remembered instead in the museum. The building that once housed donkey stables in a bustling community now serves as a lonely reminder of downtown's better days. The town's population has dwindled for decades, dropping to under 600 in the latest census count.

Jereleen Miller first ran for mayor in 2007. She promised to finish a stalled project to turn the path of the old rail line into a nature trail and to get a fire hydrant installed near a subdivision.

She lost her reelection bid four years later, then returned to power in 2015. In her time, she said, she has been careful with the town's finances, refusing to go into debt while leaning on grants. During her tenure, the town opened the walking trail, connected to sewer lines instead of using a sewage lagoon and opened the new town hall and Bethune museum.

As part of the renovations, the town told the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development it would build four apartments for low-income residents. It also committed to putting a deli and medical clinic in the building. Neither is currently operating.

To finish the deal and collect the rents, Mayesville created a community development corporation — a nonprofit setup used by towns and cities across the nation to help raise money for affordable housing and economic development.

The town turned over the deed to the property to the nonprofit. It did so to meet requirements around the housing component of the grant instead of partnering with an outside public housing agency. Ed Miller was named executive director on the new nonprofit. The position came with a salary of about $500 a month.

He also served as construction manager on the renovation project, a job that paid him $36,000.

He said the arrangement saved the town money because the only other group willing to oversee the project was going to charge $100,000. And he said he stopped taking a salary from the nonprofit after the election because people started complaining.

"We have nothing to hide," said Ed Miller, who also serves as chairman of the governor's commission on disabilities and special needs. "You build it, we take it. That's the mentality of these folks."

Wilson was the only council member who objected to having the mayor's husband benefit from the situation. The case concerning his alleged threats against the former mayor has been stalled with no resolution for more than a year.

The charges, he said, stem from a long-simmering political feud with Jereleen Miller, whose actions he constantly questioned after he was elected to Town Council in 2021. He is related to the former longtime mayor, whom she had replaced.

The Millers say they have been unfairly scrutinized by Brown and Wilson. Mayesville has a long history of patronage, with judgeships and jobs given to family members and political supporters. And in a town the size of Mayesville, it can be a tall task to find someone who isn't related to anyone in elected office.

"It's nepotism when it comes to somebody else," Jereleen Miller said, "but when it comes down to their family, it's another terminology."

An outside challenger

Brown entered the picture about two years ago. A former high school teacher and assistant athletic director at a college in Utah, he switched careers to home renovation before packing up his family and moving to Mayesville in 2022. They bought a house that was nearly falling down. Inside, they found clothing and books that revealed the house had been owned by a fellow member of the Church of Latter Day Saints. Brown has so far renovated four houses in town.

With his background in construction and development, Brown thought he had the right skills to help a town that needed rebuilding. He shared his interest with Wilson, who was planning to run for mayor at the time. Wilson opted to drop out of the race and endorse Brown.

"The town needs a whole facelift," said Wilson, who was born and raised in Mayesville. "This town don't have nothing compared to when I've been a young man."

To the surprise of many, this white political newcomer won the election in this overwhelmingly Black town.

With a vote total that exceeded the town's white population, Brown said his victory came from a wide swath of the community wanting change.

But Jereleen Miller said Brown barreled into office with preconceived notions about scandal and mismanagement.

And they said he showed his hand at a tense town meeting on Nov. 10, days before he was sworn into office.

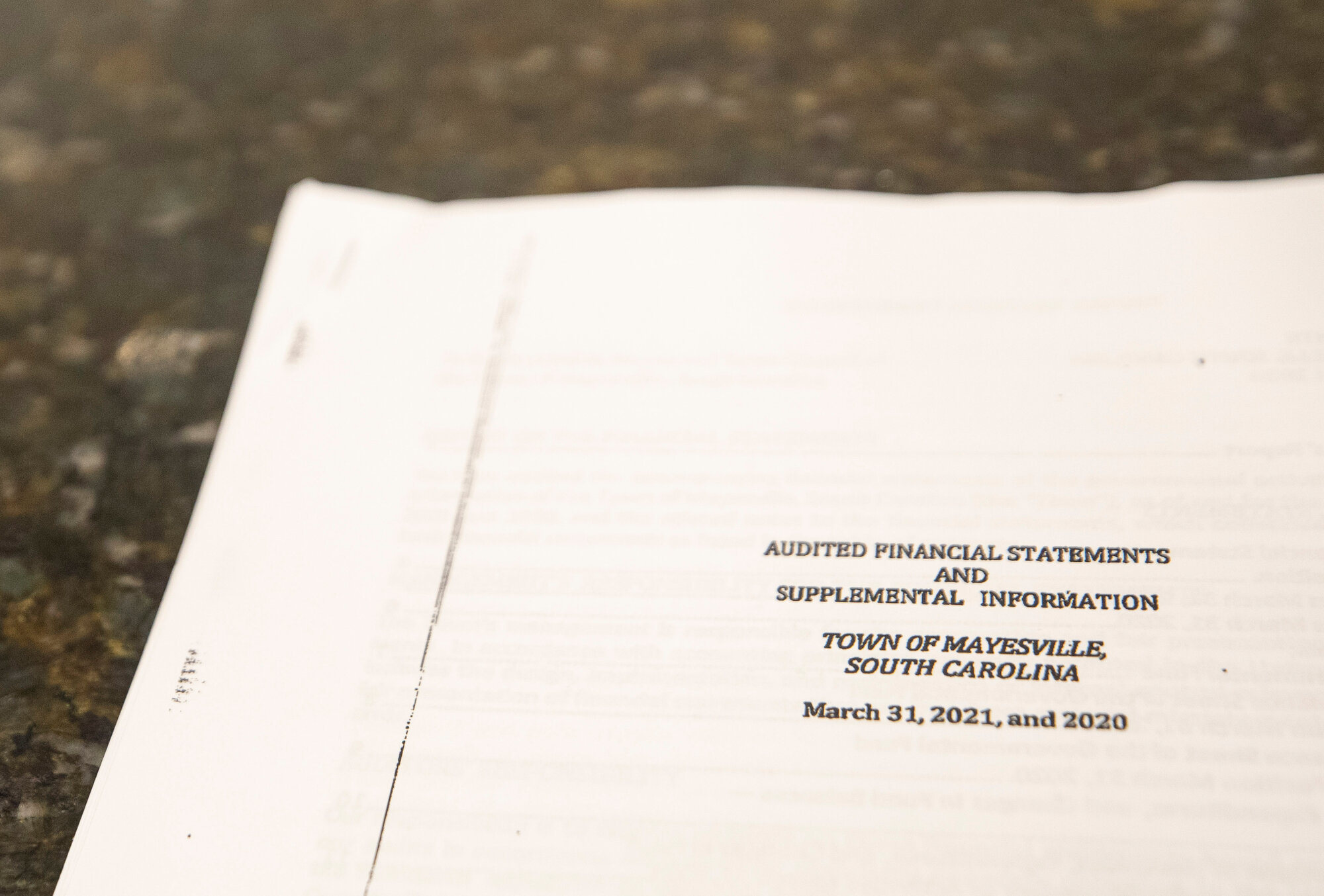

In her closing act as mayor, Jereleen Miller oversaw a special meeting with the sole purpose of giving final approval to a town audit for 2020 and 2021. Miller said two of the council members couldn't vote on the matter because they weren't in office during those years — a rule not grounded in any law.

Brown, the mayor-elect, asked to see the audit the mayor and a single councilwoman were approving. No one seemed to have a copy at the meeting, which devolved into name-calling and insults.

After Brown received a copy of the audit more than two weeks later, he showed it to the town's previous auditor, who described the document as "terrible." That auditor advised him to file a complaint with the state because the document did not include updated financials in some areas.

"They copied a lot of our report and then left a bunch of (2017-18) stuff in the report for items they didn't know how to report on — you cannot do that," the previous auditor told Brown in an email.

Brown reported the audit to the S.C. Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation. Regulators there can investigate the auditor but have no authority to require the town to complete a new audit.

Towns are required to send annual audits to the State Treasurer's Office. But the state only checks to make sure its reporting of court fines is fees are correct. No one in the office reads the full audit or checks it for accuracy.

The State Treasurer's Office said complaints like Brown's should be sent to the State Auditor's Office. But State Auditor George Kennedy said his office isn't authorized to monitor or investigate local government issues outside of issues with court fines.

No state agency is.

Mayesville's three active Town Council members did not return calls seeking comment on the matter.

And Sumter County leaders don't have much to say about Mayesville either. They noted through a county spokesman that the county sales tax money that went to Mayesville and other projects was subject to an audit that came back clean.

Vivian Fleming-McGhaney, a county councilwoman whose district includes Mayesville, wouldn't confirm or deny knowing about what's going on in the town. She said only that she loves the people of Mayesville and "we have no control over it."

Sumter County Sheriff's Office has also fielded competing complaints from both sides. But as far as they can tell, nobody is breaking the law.

"It all sounds civil to me, but I contacted SLED and asked them to look into the matter," Chief Deputy Hampton G. Gardner said. "What they're doing with it, I couldn't tell you."

Deputies couldn't force Miller to give Brown keys to the building or Brown, as mayor, to return the town records he said he took for safekeeping.

Brown and his opponents have also called the State Law Enforcement Division with competing complaints, but Brown said they told him the problems he is dealing with seem more political than criminal.

Distrust lingers

During an interview at the town hall and museum, Jereleen Miller said the audit that people are concerned about was an earlier draft than the one the town submitted to the state. But the version she had the town clerk produce had the same glaring errors.

Roy Friday, the Maryland-based auditor hired by Mayesville, had previously told The Post and Courier that allegations about the audit were false. He then hurriedly ended the interview and stopped responding to a reporter's calls and texts after that conversation.

Standing inside the room envisioned as a deli, Jereleen Miller called Friday to ask why some pages don't include updated information for the years he covered. She got no explanation.

"We'll get that straightened out," she said. "I don't know why it wasn't there because we went extensively over '20 and '21."

Even though Ed Miller's position leading the development nonprofit gives him control over access to the building, its bills — even the security cameras that he controls — are paid for out of the town budget.

Brown vowed to stop those payments.

On the same day the Millers shared their story, Brown showed off the town's abandoned old town hall — one of the only buildings in Mayesville that Mayesville still owns.

A musty smell rushed from the door as soon as it was opened. Black mold has overtaken the building, with the white paint on some walls only visible in small patches.

Brown hopes the town can make this town hall a meeting place again.

He guessed it would cost about $50,000, though there's no indication he has enough support on council to make it a reality.

Brown and the Millers haven't met since he took office. Jereleen Miller skipped the meeting where he was installed, and he hasn't been able to find a meeting time agreeable with Ed Miller to discuss the nonprofit he leads.

They don't trust him, this outsider who Ed Miller said he caught on tape sneaking into the new town hall, unplugging the security cameras and making off with records "like a thief in the night."

Brown thought he would be working by now to help the town on a wish list he compiled while knocking on every door during his campaign. People want a police force, a laundromat, a barbershop. Maybe a splash pad where children can play.

But he's quickly learning that winning an election and holding power aren't the same thing.

More Articles to Read