Uncovered: When newspapers close, bonds among locals weaken, and misdeeds can thrive.

jhawes@postandcourier.com

shobbs@postandcourier.com

Editor's note: This article is part of The Post and Courier's Uncovered project. To read more investigations from it, CLICK HERE.

***

UNION — Deadline looms at the weekly Union County News, where Graham Williams puts final touches onto one of the thickest editions he will print all year — 28 pages, with a special football section. Readers love high school football.

He pokes on a pair of tortoiseshell reading glasses and peers at his computer monitor. Somewhere in the pages he has laid out, a child’s name is misspelled, a miraculously rare event given the volume he prints. Readers love seeing their kids’ names in the paper.

"Where is it?" he asks, then finds it and fixes it. Readers also expect accuracy.

His wooden desk, bibbed with stacks of folders and paper, faces the newspaper’s glass front door. Beyond it bustles Main Street, where he spots Anna Brown sprint-walking toward him. She rushes inside to grab a camera before leaving again to take headshots of student athletes.

Brown is the newspaper’s publisher, and Williams its editor, but “these are really just titles,” he says. In a two-person shop, each does whatever needs doing, although how long they can keep it up remains uncertain.

His desk phone jangles. A woman on the line wants a copy of a family member’s obituary. Minutes later, she stops by.

She lives in Texas but is visiting this hilly old mill town, tucked in upper South Carolina, to deal with her relative’s probate. As she relays problems she is having with the process, Williams takes mental notes. It could be a future story.

He hands her a small stack of papers containing the tangible memory of her loved one’s death.

“Anything else, just call us.”

In a day when partisan warfare and Twitter taunts can define the day’s public discourse, local newspapers like this one provide something else. They bind people with the glue of shared community.

Obituaries tell readers who died in town. Legal notices alert them to public meetings and court proceedings. Sports stories announce whose kid caught the big pass Friday night. Or who fumbled it.

Yet, increasingly, that community glue is drying up.

Take Union County where, if not for Brown and Williams, there would be no local newspaper.

Their competitor, the once-daily Union Times, folded last year. After reporting on the Civil War, the Great Depression, two world wars and 170 years of other news, the financial strain of COVID-19 finally broke it, the editor wrote in a farewell column.

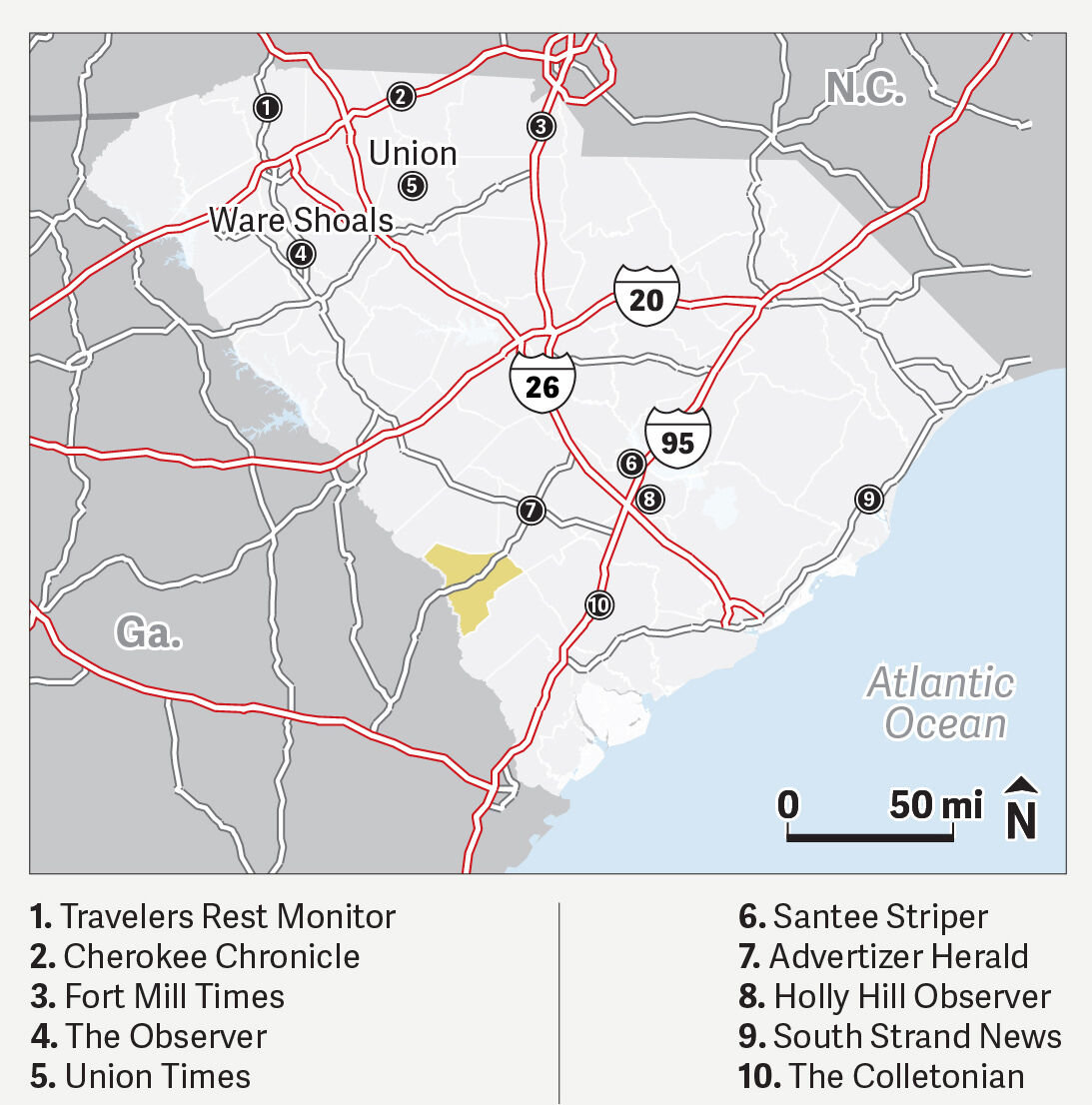

The Union Times was one of 10 papers across South Carolina that stopped printing in 2020. The year marked a record loss, at least in recent memory, said Jen Madden, co-executive director of the S.C. Press Association.

Familiar antagonists — financial stressors, professional moves and retiring overseers — threw most of them over the precipice of viability.

Their closures cut news coverage for people living in every corner of the state: Ware Shoals, Bamberg, Santee, Holly Hill, Fort Mill, Walterboro, Georgetown and Union. Two of the 10, in Gaffney and Travelers Rest, at least still provide online coverage.

The glue that is lost doesn’t only bind readers. Without journalists shining light on public officials’ actions, corruption and misdeeds can thrive. The Post and Courier has unearthed myriad examples of questionable conduct during its yearlong investigation, Uncovered.

Rural gas authority officials in York County jetted to far-flung locales to dine with their spouses at pricey restaurants on the taxpayers’ dime. A Clarendon County school district used money meant to recruit teachers to buy a townhouse, then let its superintendent live in it rent-free for months.

In Allendale County, where both local newspapers closed in recent years, the state has taken over the school district for the second time. Three area public officials have gone to jail on embezzlement charges. And the State Law Enforcement Division is investigating the findings of a forensic audit of the county that revealed severe accounting deficiencies.

As Williams finishes laying out the Union paper’s pages, a framed copy of its first edition, published in 2009, hangs on a beige wall over his shoulder: “Clerk of Court Brad Morris has resigned amid a SLED investigation of accounts managed through his office …”

Brown and Williams have loved their work. They know its importance.

But they cannot do it forever.

Williams just turned 67 and hopes to retire in a few years. Brown is 57. What will happen to this newspaper — and the nearly 30,000 people who live in Union County — when they go?

They haven’t discussed it.

The possibilities are too painful, and they are too busy.

Williams emails his pages to a print shop in North Carolina, then dashes home for a tomato sandwich, then rushes to a 6 p.m. school board meeting. God knows how late the meeting will go. The board loves executive sessions, he says — and he has pledged never to leave before they take their final votes.

When glue is gone

An hour’s drive southwest of Union, another rural town is learning what is lost when a local newspaper dies.

In Ware Shoals, copies of The Observer sit on a metal stand inside the newspaper's dusty offices like a historical marker. A headline in the paper, dated Dec. 2, 2020, reads: “The Observer announces plans to suspend publication immediately.”

Thousands of other yellowing pages documenting decades of local news languish in unkempt mounds behind it.

Four months before writing that headline, Publisher Dan Branyon was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. He and his wife, Faye, the paper's reporter and editor, kept publishing as he endured chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

They persevered until Dan felt like he had razor blades down his throat. He lost 35 pounds in 30 days.

One night, sitting at his computer, he told Faye: “I just can’t do it anymore.”

It broke their hearts. Both Ware Shoals natives, they had started the paper in 1981 because they felt town issues had gone uncovered for too long. Four decades later, they hated to let their community down.

Indeed, the aftermath of newspaper closures can reach far and cost plenty.

Ed Farr, a funeral director and former longtime school board member, recalled how Faye kept public officials on their toes, even calling him out when necessary. “She was faithful to report exactly what was going on."

Faye had covered virtually every town council and school board meeting. Without her, there isn’t always a journalist monitoring Ware Shoals meetings anymore. Reporters from the daily Index-Journal in Greenwood go to many of them, but Ware Shoals has only about 2,000 people, and the newspaper has many other places to cover.

Then there are the financial costs to losing a local paper. In 2018, researchers found that newspaper closures led to higher borrowing costs for local governments, plus increased taxes and deficits due to the loss of a community watchdog.

Jobs vanish, too. Since 2004, about half of print journalists have lost their posts, according to “Vanishing Newspapers,” a research project at the University of North Carolina.

But so much of what is lost cannot be calculated in jobs, tax dollars or corruption.

It is measured in glue.

Lamar Smith made his home outside of Ware Shoals for more than 65 years. The 90-year-old lives in Greenville now, but he kept track of friends and events in his hometown by reading The Observer.

“When the paper shut down,” Smith said, “it seemed like the whole town shut down with it.”

Keith Davenport also subscribed for years. Without the paper, the 76-year-old feels adrift. A good friend recently died but was already buried by the time he heard about it. He felt awful.

Farr, the funeral director, asked someone at church if the high school football team had a game yet. Turned out, they’d played a few nights earlier. He missed it.

The Observer also used to run a group picture of the local high school’s graduating seniors on the front page. Readers would cut it out and save it in scrapbooks, recorded family history.

This year, nobody ran the photo.

Binder of people

Williams sits at a table inside Union County’s school board meeting room, his tools spread before him: reporter’s notebook, cellphone, tape recorder. A radio reporter sits beside him, but no other newspaper journalists are covering the meeting.

The superintendent explains that it is only the first day of school, but 48 students and 11 staff in the small district already are quarantined or have tested positive for COVID-19.

District leaders support wearing masks, he says, but can only encourage them. A budget proviso bars districts from using state funds to enforce mask mandates.

Trustee Manning Jeter proposes requiring masks in schools, regardless. “I’m talking about the health of our students,” he says.

As board members launch into a debate over Jeter's proposed mask mandate, Williams takes notes, black pen scrawling across a reporter’s notebook.

The vote fails 5-3.

Grabbing his cellphone, Williams types a few lines and posts the vote on the newspaper’s Facebook page. It fills with comments as local readers hear the news.

After the board members work through their agenda, they go into executive session. Williams lingers in the hallway, prepared to wait them out. If reporters like him didn’t do so, the public would only hear what political leaders want them to hear.

“Then we’d be in bad shape,” he says.

His love for the business began in middle school when he delivered newspapers. In high school, he wrote for the paper in his hometown, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He studied journalism at the University of North Carolina, then came to Union four decades ago. He made $15,000 a year.

He and Brown worked for the now-defunct Union newspaper until 2009, when they both left dissatisfied with its local coverage. Brown and her husband put up the capital to start the Union County News, and Williams joined her.

They have remained committed to journalism’s watchdog role.

Last year, Brown used the state’s public records law to pursue documents that exposed complaints that then-Union County Sheriff David Taylor had sent lewd messages and asked subordinates to buy him alcohol while on duty.

At first, a SLED employee told Brown the public records would be pricey to gather and redact.

“Will y'all be able to handle it?” the woman asked.

Brown retorted: “We sure will.” She pledged to scrounge the money from her own pocket, if necessary.

In the end, the state didn’t charge for the records. The sheriff was indicted for allegedly sending lewd messages and an obscene photo to a citizen. Prosecutors dropped the charges this summer, “but officials won’t give a reason why,” Brown reported at the time.

Outside the school board meeting, Williams waits until 9 p.m. When the board members return to open session, they vote to raise substitute teacher pay.

It is long after dark when he slips into bed. At sunrise, he will head back to the newspaper to deliver copies himself, wondering how much longer he can work at this pace.

Long odds of survival

Back in Ware Shoals, Dan Branyon could not come up with a succession plan for The Observer before it stopped publishing. The 67-year-old's two children did not pursue journalism careers. And none of the young reporters who had worked at the newspaper over the years stuck around.

“There’s not a whole lot to hold people in a small town,” Branyon said.

It’s a huge challenge across the nation, especially in rural states like South Carolina.

“The papers are doing the best they can, but you wonder if they will be able to make it," said Madden of the S.C. Press Association.

Since 2004, the nation has lost a quarter of its newspapers. That’s 70 dailies — and more than 2,000 non-dailies, according to “Vanishing Newspapers.” Most served smaller areas like Ware Shoals and Union.

The South has been hit especially hard. Every state in the region, including South Carolina, has at least one county without any newspaper at all.

Tight margins are a huge challenge. But another key problem is that many small newspaper owners lack plans for the future, said Jim Iovino, program director of NewStart, a local news ownership initiative at West Virginia University. The yearlong fellowship trains people who are interested in running their own publications in rural areas, then connects them with owners interested in selling.

Last year, six students took part in the program’s inaugural class. This year’s group has seven, although none from South Carolina.

“If a paper closes,” Iovino said, “that sense of community, in and of itself, kind of disappears and dies.”

To fill voids around lower South Carolina, Andrew O’Byrne has launched community weeklies in places that have lost newspapers. He published his first one in Aiken County about a decade ago and now runs five more.

Last year, O’Byrne and his son started the Bamberg County Leader and the Orangeburg Leader to cover the Bamberg area, Holly Hill and Santee areas after longtime weeklies in those places closed their doors. O’Byrne said he operates on tight margins but believes strongly in the value of printed newspapers that record history in ink for the ages.

“There is a commitment there,” he said. “You can find an old newspaper, and it still says what it said on the day it was printed. You can’t erase it.”

Community contributors and freelance writers produce most of his content while O’Byrne, his son and wife “pack in the hours to make up the difference.”

Why? “Because people still need a newspaper."

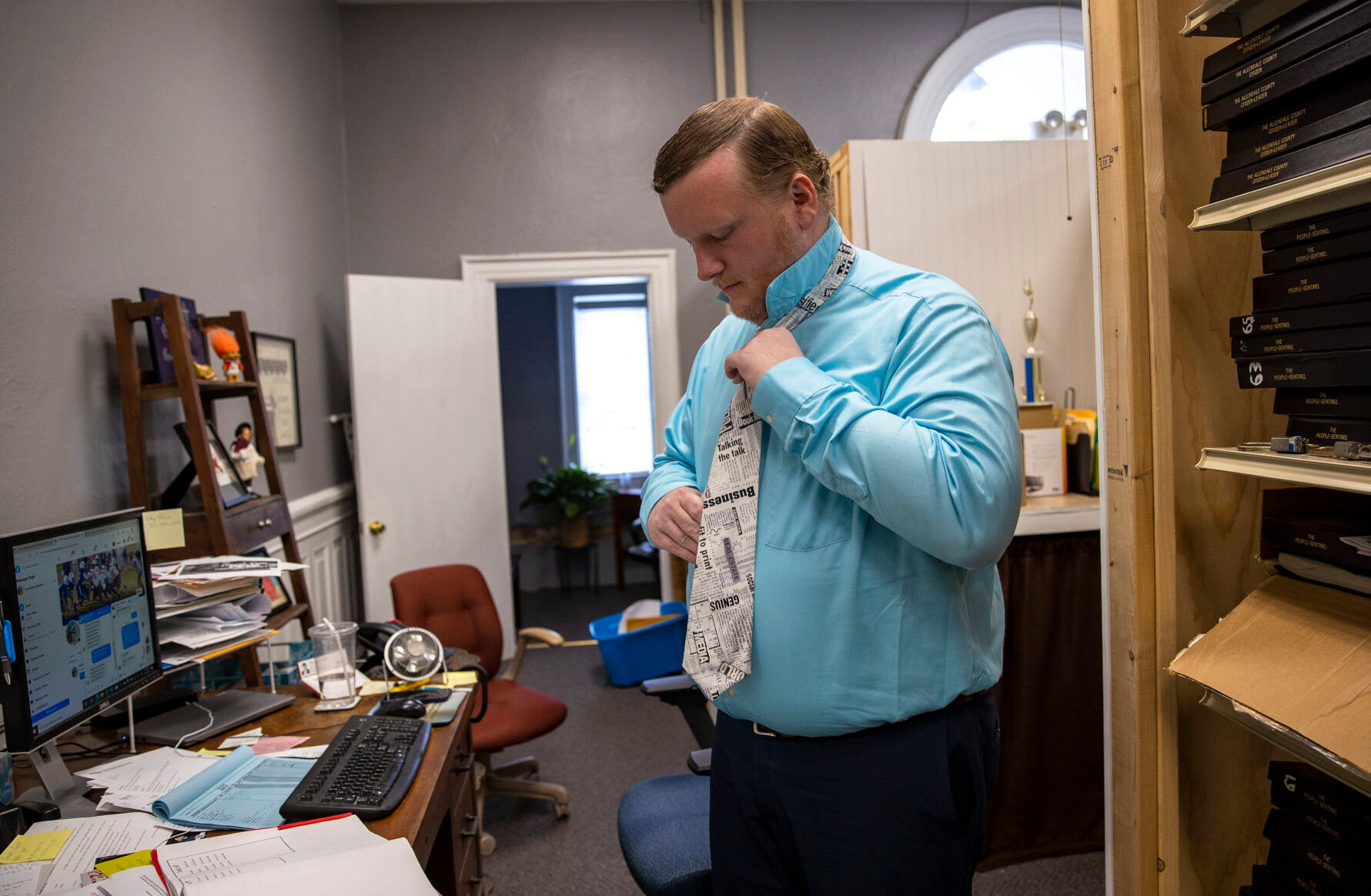

In nearby Barnwell County, a 33-year-old journalist took his hometown paper’s future into his own hands: He bought it.

Jonathan Vickery purchased The People-Sentinel from a subsidiary of Gannett, the largest newspaper chain in the country, then took the helm on July 1.

Vickery, who has worked at the paper since 2010, declined to specify the purchase price. But he did explain how he enlisted friends, now his business partners, to invest in it.

Since he took over, more than 120 people have bought new subscriptions. Others wrote notes of thanks. He picked up new advertisers.

So far, he employs four people and has hired new freelancers. One covers neighboring Allendale, the state’s lone news desert.

“It’s important to let our readers know how their tax dollars are spent, what policies are being put in place, what motions or actions their public officials are taking that will potentially affect their families,” he said.

Vickery’s track record speaks to that. He has already won the state press association’s Assertive Journalism Award — twice.

Recorders of history

At 7:28 a.m., Williams returns to the Union newspaper’s office after covering the late school board meeting. The week’s freshly printed edition sits in stacks, and he must help deliver them.

Brown, the publisher, is already several hours into her nearly nine-hour delivery route.

A few carriers come and go from the office, a thin space tucked between a knickknack shop and a jeweler. Roger Harris, an 87-year-old carrier, sits rolling newspapers at a table near a refrigerator stocked with Nutter Butter cookies and cans of Sun Drop soda.

His canvas bag full, he stands and heads out. A wiry man in jeans, his leather belt bears a large American flag buckle. He has delivered, literally, millions of newspapers during his career.

“Y’all stay sober!” he calls.

In back, Williams whistles while slapping address stickers onto the 366 papers — about 10% of the News' circulation — that get mailed to people far beyond Union who want to keep tabs on local news.

The week’s front-page stories discuss a ceremony for the Sept. 11 anniversary, a new hydraulics company in town and a local cheer coach being honored. It is news readers care about — and would be hard-pressed to find anywhere else.

Williams fills four industrial-sized plastic bags that he will haul to the post office. But first he must tackle the Main Street delivery route.

When he steps outside, a man driving by honks and hangs an arm out to wave.

Williams knows everyone. And everyone knows him.

Spry in cargo shorts and tennis shoes, he zips along on foot with a bag of papers, greeting people. As he goes, he rattles off stories he has written about seemingly every patch of dirt, every brick, every windowpane he passes.

Nowhere do the old memories blare more loudly than from the historic courthouse, where the biggest news in Union’s modern history took place: the 1995 trial of Susan Smith.

The 23-year-old was convicted of murdering her two little boys by driving their car into a local lake, then letting it slowly sink with them strapped inside. The case drew intense national coverage in part because, before she confessed, Smith claimed that a Black man had kidnapped her sons during a carjacking.

Williams remembers how hundreds of reporters flocked to Union to cover her trial. National outlets interviewed him to find out what was going on.

His beard has gone grey since, but he still sprints up the steps to the courthouse where it all took place. Just outside the courtroom where Smith was tried, he chats with a deputy who mentions that they haven’t done a fire drill in this old building for as long as he knows.

Williams wonders: Could that be a story?

Sweat dampens his Fenway Park T-shirt by the time he heads back to the newspaper office.

When he arrives, employee Rick Drain is running a couple of large color copy machines where they print everything from church letterhead to posters. It helps pay the bills.

Yet, despite so much sweat and caring, the newspaper hasn’t turned a profit in years.

Paying the bills

Even before Dan Branyon got sick, the newspaper's finances created constant stress.

For at least a decade, The Observer didn’t even bring in enough money to pay him or Faye a salary. Dan held another job for many years while putting the paper out. He was director of public relations for a local hospital.

Subscription and advertising sales did not cover The Observer's printing and delivery costs. Printing and mailing alone could cost $500 a week on top of utilities. Piggly Wiggly ads that once filled two full pages got smaller and smaller over the years.

The couple used their own money to pay the difference.

But they still kept the price low: 35 cents a copy or an annual subscription for $16.50. They didn't charge for death notices. They ran birth, anniversary, wedding and engagement announcements for free.

Yet, this glue that once bound Ware Shoals residents — coverage of the graduations, the elections, the triumphs and the hullabaloos — might vanish forever.

The Ware Shoals Community Library has boxes filled with old Observers, but not all of them. And the state library doesn't have copies archived at all.

Watchdogs are watching

With the newspapers delivered, the Union County News staff cranks forward into a new week, another deadline. At church, Brown hears that a newly reelected city councilwoman has moved out of her district.

She passes the tip to Williams.

He starts to dig at the tax assessor website. He calls the city administrator. He zips to the courthouse and stops by the tax office, then heads to city hall to talk with the clerk.

Indeed, Councilwoman Vicki Morgan bought a house in another district and appears to be living there.

He calls her. She admits she moved but thought she could live anywhere in the city after getting elected. Williams reads her the Municipal Association of South Carolina’s handbook.

“You’ve moved into somebody else’s district,” he says.

He writes the story and types his headline: “Morgan may have to resign from council.”

Just hours before his deadline, the councilwoman walks into the newspaper office. She tells Williams that she will resign.

“That’s my story,” he thinks.

This is why he got into the newspaper business: to reveal truth, to provide news, to glue his community together. He might be headed toward retirement, and this newspaper might go with him, but the Union County News hasn’t gone anywhere yet.

Glenn Smith contributed from Charleston.

More Articles to Read